The Reverse Mapping

Each process in Linux has its own dedicated virtual address space to keep track of the memory in use, this is known as mapping memory into a process.

Some of what’s mapped is backed by files, and some if it is backed by the swap (i.e. anonymous memory), but everything that is mapped and present ultimately connects the virtual memory to physical memory within the system, that is RAM.

When I say ‘backed’ here ultimately I mean – if memory is reclaimed and then later needs to be restored to memory – where is the memory restored from?

For file-backed mapped memory this is, of course, the files on disk. For anonymous memory, this is the swap.

Of course often the swap doesn’t span all available anonymous memory, once it is full then further anonymous simply cannot be swapped out until memory in the swap is restored.

The separation of virtual and physical address spaces allow for each process to both own an entire virtual memory area, and share physical memory with other processes.

In order to tie the two together, the kernel maintains a series of hardware-specific data structures called ‘page tables’ arranged such as to provide a sparse (that is space-efficient given most virtual memory remains unmapped) mapping between the two.

The mappings are maintained in a sparse representation tying virtual addresses to physical addresses called page tables.

Page tables are essentially arrays which maps spans of virtual memory to physical addresses of page tables, in a hierarchy, with each ‘level’ mapping a narrower range of memory.

At the lowest level page tables entries, so-called ‘leaf’ entries, map to the actual physical memory addresses (each at a granularity known as the ‘page size’).

Since the page tables span as large a range as they possibly can, narrowing only in range when memory is actually mapped we achieve lower overall system memory use by the mappings themselves.

The kernel stores metadata for both physical and virtual memory, which we will discuss in more detail below.

This is necessary, as part of the kernel’s job is to manage and fairly distribute resources, and physical memory is one of those resources it must manage.

Equally, virtual memory needs to be tracked for each process to inform the CPU of the different virtual memory layout when a context switch occurs.

Within the kernel there are key mechanisms which rely on providing a bridge between the worlds of virtual and physical memory.

The most notable mechanism is reclaim, which is used to free up less frequently used memory when usable memory is running low. Reclaim prioritises more frequently used memory when it is in higher demand.

We also need to maintain a bridge in the opposite direction; physical to virtual, for reclaim as, when physical memory is freed, we need to update page tables to reflect that the memory is no longer mapped.

More generally, this bridge is called the ‘reverse memory mapping’, as opposed to the ‘forward’ memory mapping, which consists of page tables mapping virtual memory to physical.

File-backed memory differs from anonymous memory in how the reverse mapping is implemented – the kernel keeps track of every page of file-backed memory at a lower level of abstraction handled by the storage layer and the representation of the mapping from physical memory to virtual is simple and direct.

The anonymous memory reverse mapping however is far more complicated, which this blog post explores in detail.

The Anonymous Reverse Mapping

Physical memory metadata is represented in the kernel by folios. There is one folio for each independently userland mappable range of physically contiguous memory up to a limit of, typically, 2 megabytes.

Virtual memory ranges are represented by Virtual Memory Areas, or VMAs.

When a VMA is first faulted in it establishes an abstracted representation of the anonymous reverse mapping – represented by the anon_vma type (excluding comments):

struct anon_vma {

struct anon_vma *root;

struct rw_semaphore rwsem;

atomic_t refcount;

unsigned long num_children;

unsigned long num_active_vmas;

struct anon_vma *parent;

struct rb_root_cached rb_root;

};For simplicity let’s focus on the rb_root field – this is a kernel type which acts as the root of a red-black interval tree which links anon_vma objects to anon_vma_chain objects (again, excluding comments):

struct anon_vma_chain {

struct vm_area_struct *vma;

struct anon_vma *anon_vma;

struct list_head same_vma;

struct rb_node rb;

unsigned long rb_subtree_last;

};Fundamentally this acts as ‘glue’ between a VMA and an anon_vma. The rb field is the red/black interval tree node, and same_vma is a list head which allows for multiple anon_vma_chain (or ‘AVC’ for short) objects to be connected from one VMA to multiple anon_vma_chain objects – we’ll get into why shortly.

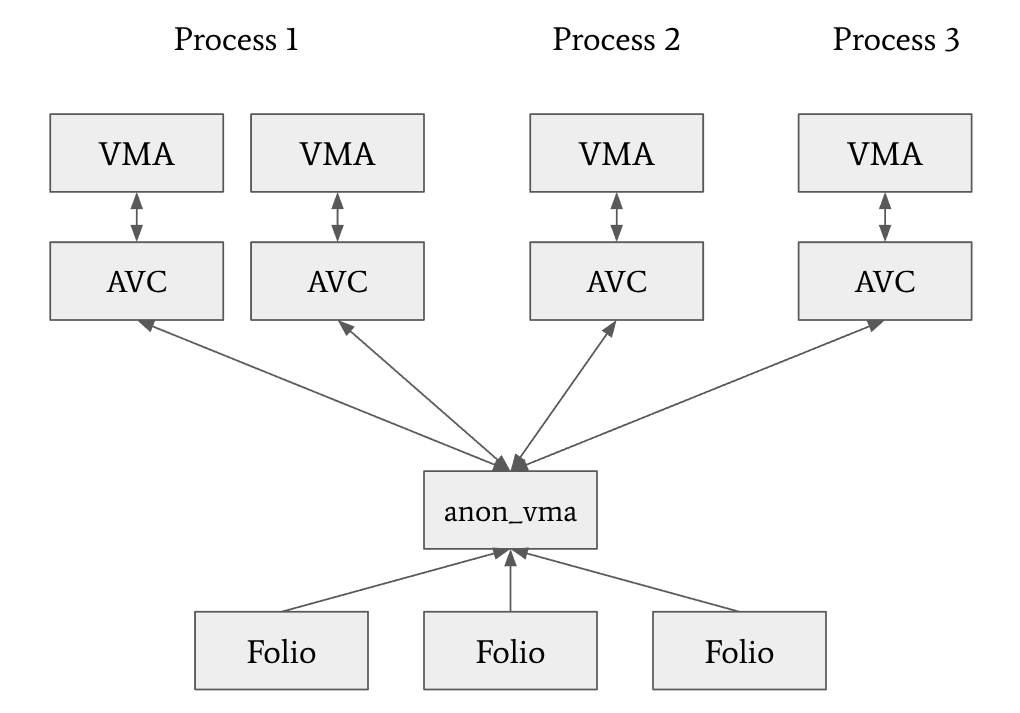

So broadly speaking the representation looks like this:

Where a folio uses its index field to track the offset of the start of the folio within the range the anon_vma encompasses, and its mapping field to store a pointer to the anon_vma itself.

This way, we can go from a folio to an associated VMA by:

- Looking up the

anon_vmafrom the folio. - Looking up the

anon_vma_chainusing the red/black interval tree inanon_vma->rb_root, starting at page offsetfolio->indexand ending at page offsetfolio->index + folio_nr_pages(folio) - 1(wherefolio_nr_pages(), as the name suggests, determines the number of base pages the folio spans). - Looking up AVCs found in this range and obtaining the relevant VMAs via the

anon_vma_chain->vmafield.

Why might there be multiple VMAs that a folio might reference? Well, while the anon_vma is associated with the VMA range upon first faulting in a page within the virtual range, the VMA can change over time.

Unmapping in the middle of the VMA for instance will split a VMA, or alternatively it might get merged with adjacent VMAs or even moved via mremap().

We must be able to maintain a coherent anonymous reverse mapping in all such cases.

Forking

Most important of all though is that we need to take into account forking. When a process forks, we try to be as efficient as we can both in terms of time taken and memory used.

Upon fork, virtual memory metadata describing faulted-in anonymous memory is always copied along side page tables mapping them to physical memory, though folios describing the physical memory are not.

This is because, rather than duplicating all the data (which may never change, or even be used), the page tables are copied and updated such that they are read-only in both the parent and child process.

Then, when the user tries to read from this memory in either the parent or the child, both read from a single source of data, without having to duplicate it. This approach is called Copy-on-Write (or CoW for short).

But, since the page tables are marked as read-only, if either process writes to the memory, it results in a page fault and the kernel will copy the relevant data.

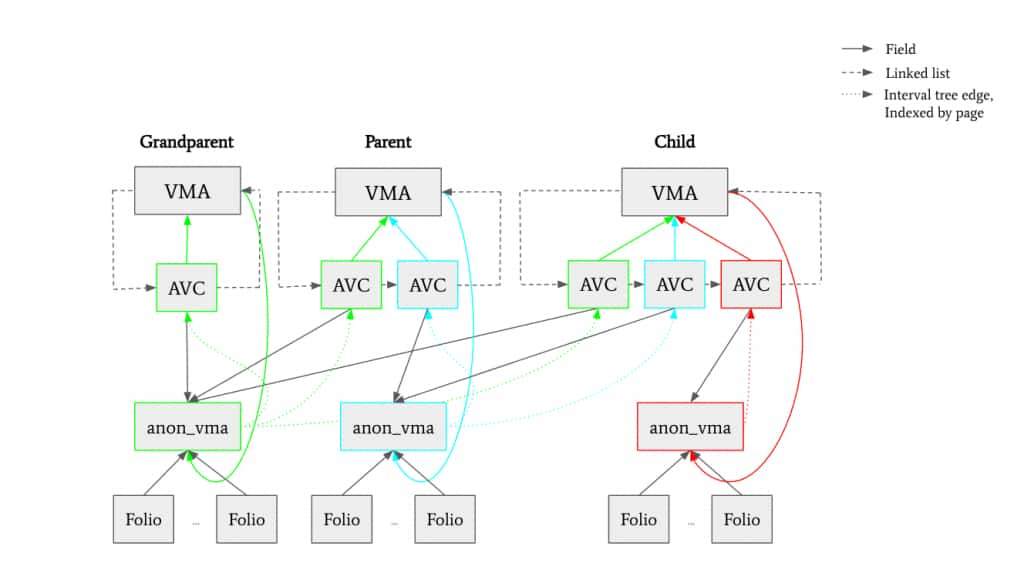

Supporting this makes the anonymous reverse mapping substantially more complicated – we need to track both the VMAs that map the data in the parent and the VMAs that map the data in the child as now one folio can be associated with both.

And of course processes can keep forking, thus creating large hierarchies of anonymous reverse mapping metadata.

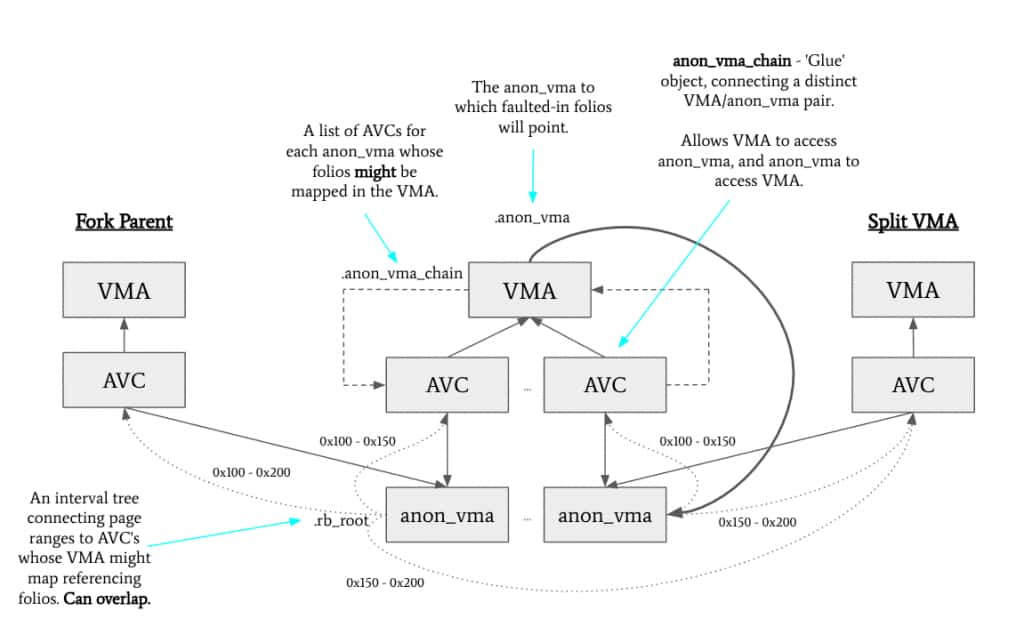

Visualising this:

The diagram shows the list of associated AVCs per-VMA, which includes the encoded fork hierarchy – with the first entry being the most distant ancestor and the last entry being the anon_vma with which faults occurring in the child will associate new folios with.

And looking at a more focused forking example:

Note that the only time we add an AVC to a VMA is during a fork. All other operations which cause cloning of AVC objects – merge, split, remap – simply copy existing entries to the newly merged/split/remapped VMA to maintain the association between anon_vma objects and VMAs.

Locking

As we manipulate interval trees connecting an anon_vma with all of its ancestor VMAs all the way to the root of the forking hierarchy, we maintain a read/write semaphore lock across the entire hierarchy.

Each anon_vma object connects to its immediate ancestor via the parent field, and the most distant ancestor via the root field. The lock used is root->rwsem.

This can be problematic in deep hierarchies, as merges, splits and remaps are relatively common operations each of which take a write lock on this semaphore, thereby excluding readers.

For instance, see [DISCUSSION] anon_vma root lock contention and per anon_vma lock for details of a report of just such an issue.

mremap()

The reverse mapping must be updated during remap operations to maintain the ability to look up VMAs from folios.

This is relatively straightforward for file-backed mappings as the indexes referenced by each folio refer to a page offset within the file.

This is not the case with anonymous memory – the virtual page offset is set to the virtual address of the start of the folio when first faulted in, divided by the page size.

Thus when we move a faulted-in anonymous VMA, we are left in the awkward position of either having to update the folio’s index, or somehow accounting for the fact that the index will now not be related to the address the VMA is now mapped at.

Unfortunately, updating the folio is absolutely out of the question – traversing the page tables to do so is difficult, and ensuring stability of the folio and the correct locking is egregiously difficult.

I tried to implement something along these lines previously, see mm/mremap: introduce more mergeable mremap via MREMAP_RELOCATE_ANON, however this turned out to be impractical.

Therefore the kernel allows the folio index to fall out of sync with the VMA. We manage this by keeping track of the virtual page index of the start of the VMA when first faulted in via the vma->vm_pgoff field.

Then, when we access a VMA, we determine the relative offset into the VMA by calculating folio->index - vma->vm_pgoff.

Typically mremap() has the requirement that the input range must not cross VMA boundaries. However I added an exception such that, when moving VMAs only (no resizing), this requirement is relaxed, see mm/mremap: permit mremap() move of multiple VMAs.

This allows for cases where a user is moving VMAs around and simply wouldn’t be aware that VMAs might get split based on anon_vma instantiation.

Merging

This becomes problematic however when it comes to VMA merging.

When we try to merge two VMAs, for them to be contiguous, the vma->vm_pgoff field of the right-most VMA in each VMA pair must be equal to prev->vm_pgoff + (prev->vm_end - prev->vm_start) / PAGE_SIZE of the VMA to its left, i.e. they must be contiguous in terms of the virtual page offset.

Naturally it then becomes very difficult, unless a VMA is moved back to where it originated, to obtain a merge between remapped VMAs once faulted in.

Another requirement is that adjacent VMAs that are both faulted-in must have identical ‘anon_vma’ objects, which means VMAs faulted separately can never be merged.

These kinds of requirements can be very confusing for users who simply see memory that appears that it ought to be mergeable simply not being so.

I have implemented changes that permit more anonymous between unfaulted and faulted memory, see fix incorrectly disallowed anonymous VMA merges, but the faulted/faulted case remains problematic.

The Future

What I’ve described here only scratches the surface of the complexity contained within the anonymous reverse mapping which I feel has a lot of potential for rework.

I believe it’s possible to improve performance, increase flexibility and reduce memory footprint.

I have started making efforts in this direction with a foundational series, mm: clean up anon_vma implementation, which already works towards reducing lock contention during anonymous reverse mapping operations.

Early performance testing indicates a 14% improvement in throughput under certain workloads as a result of this change in locking.

I am currently researching alternative data structures and abstractions, and plan to make larger changes in the future that should address issues around locking, memory usage and more.