A Practical Guide to Choosing the Right Memory Substrate for Your AI Agents

Key Takeaways:

- Don’t conflate interface with substrate. Filesystems win as an interface (LLMs already know how to use them); databases win as a substrate (concurrency, auditability, semantic search).

- For prototypes, files are hard to beat. Simple, transparent, debuggable—a folder of markdown gets you surprisingly far when iteration speed matters most.

- Shared state demands a database. Concurrent filesystem writes can silently corrupt data. If multiple agents or users touch the same memory, start with database guarantees.

- Semantic retrieval beats keyword search at scale. Grep performance degrades on paraphrases and synonyms. Vector search finds content by meaning, this is critical once your knowledge base grows.

- Avoid polyglot persistence. Running separate systems for vectors, documents, and transactions means four failure modes. Oracle AI Database simplifies your memory architecture.

AI developers are watching agent engineering evolve in real time, with leading teams openly sharing what works. One principle keeps showing up from the front lines: build within the LLM’s constraints.

In practice, two constraints dominate:

- LLMs are stateless across sessions (no durable memory unless you bring it back in).

- Context windows are bounded (and performance can degrade as you stuff more tokens in).

So “just add more context” isn’t a reliable strategy due to the quadratic cost of attention mechanisms and the degradation of reasoning capabilities as context fills up. The winning pattern is external memory + disciplined retrieval: store state outside the prompt (artifacts, decisions, tool outputs), then pull back only what matters for the current loop.

There’s also a useful upside: because models are trained on internet-era developer workflows, they’re unusually competent with developer-native interfaces repos, folders, markdown, logs, and CLI-style interactions. That’s why filesystems keep showing up in modern agent stacks.

This is where the debate heats up: “files are all you need” for agent memory. Most arguments collapse because they treat interface, storage, and deployment as the same decision. They aren’t.

Filesystems are winning as an interface because models already know how to list directories, grep for patterns, read ranges, and write artifacts. Databases are winning as a substrate because once memory must be shared, audited, queried, and made reliable under concurrency, you either adopt database guarantees or painfully reinvent them.

In this piece, we give a systematic comparison of filesystems and databases for agent memory: where each approach shines, where it breaks down, and a decision framework for choosing the right foundation as you move from prototype to production.

Our aim is to educate AI developers on various approaches to agent memory, backed by performance guidance and working code.

All code presented in this article can be found here.

Understanding Agent Memory and Its Importance

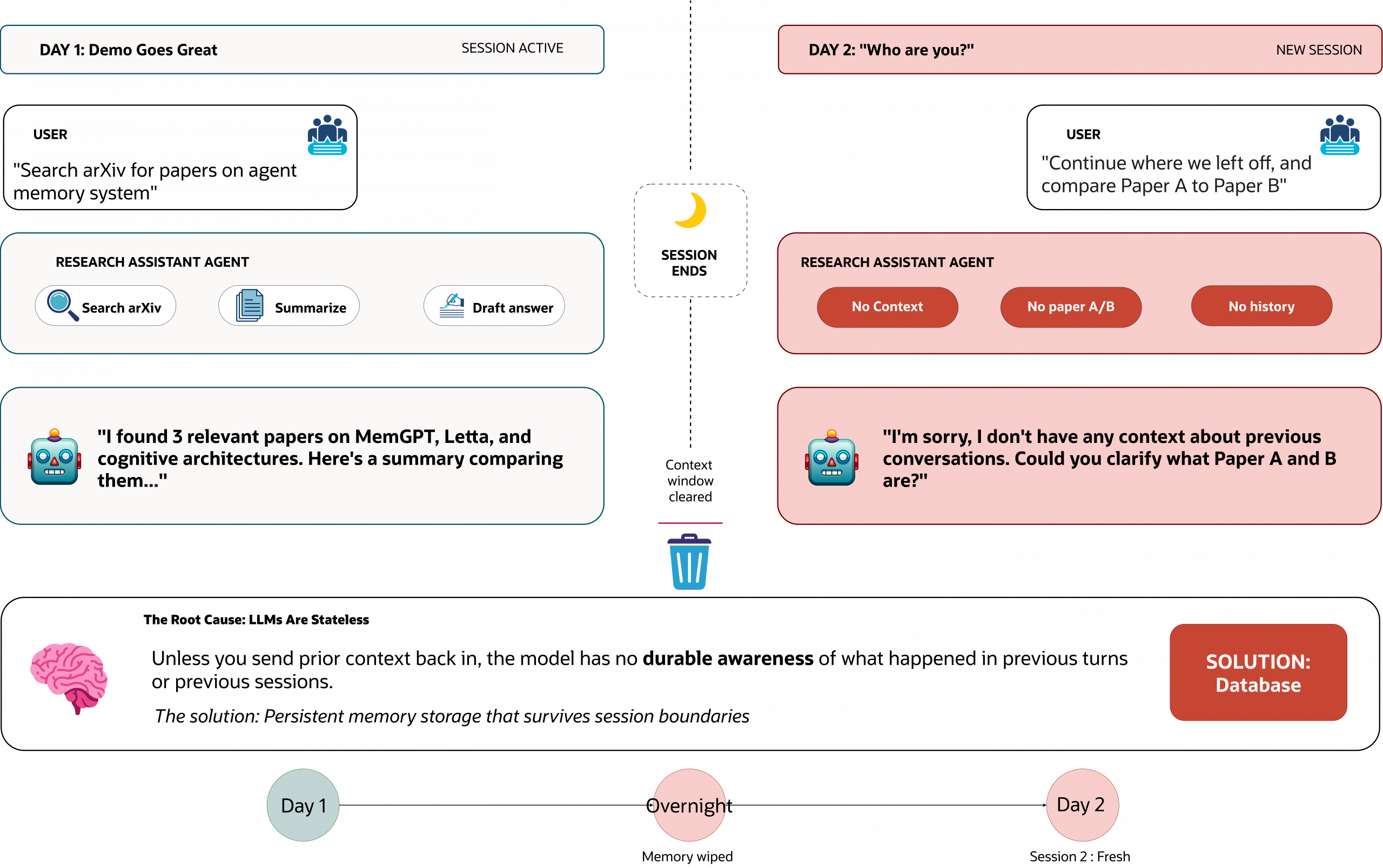

Let’s take the common use case of building a Research Assistant with Agentic capabilities.

You build a Research Assistant agent that performs brilliantly in a demo; in the current execution, it can search arXiv, summarize papers, and draft a clean answer in a single run. Then you come back the next morning, start from a clean run, and then prompt the agent: “Continue from where we left off, and also compare Paper A to Paper B.” The agent responds as if it has never met you because LLMs are inherently stateless. Unless you send prior context back in, the model has no durable awareness of what happened in previous turns or previous sessions.

Once you move beyond single-turn Q&A into long-horizon tasks, deep research, multi-step workflows, and multi-agent coordination, you need a way to preserve continuity when the context window truncates, sessions restart, or multiple workers act on shared state. This takes us into the realm of leveraging systems of record for agents and introduces the concept of Agent Memory.

The Stateless LLM Problem

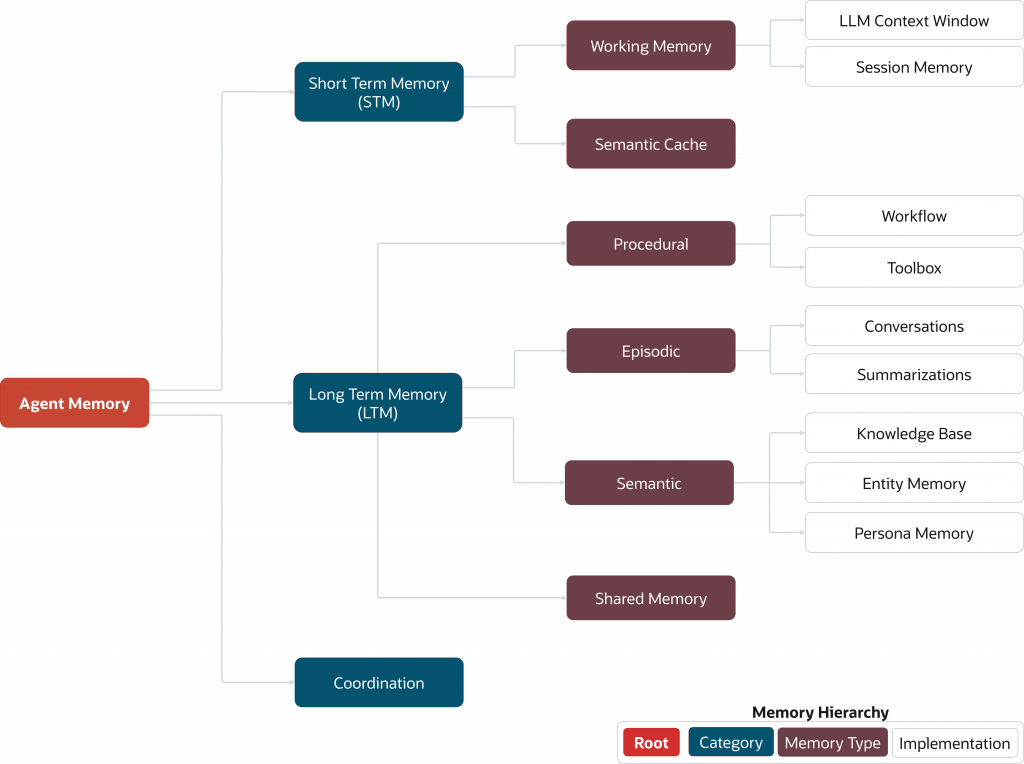

What is Agent Memory?

Agent memory is the set of system components and techniques that enable an AI agent to store, recall, and update information over time so it can adapt to new inputs and maintain continuity across long-horizon tasks. Core components typically include the language and embedding model, information retrieval mechanisms, and a persistent storage layer such as a database.

Types of Agent Memory

In practical systems, agent memory is usually classified into two distinct forms:

- Short-term memory(Working memory): whatever is currently inside the context window.

- Long-term memory: a persistent state that survives beyond a single call or session (facts, artifacts, plans, prior decisions, tool outputs).

Concepts and techniques associated with agent memory all come together within the agent loop and the agent harness, as demonstrated in this notebook and explained later in this article.

Agent Loop and Agent Harness

The agent loop is the iterative execution cycle in which an LLM receives instructions from the environment and decides whether to generate a response or make a tool call based on its internal reasoning about the input provided in the current loop. This process repeats until the LLM produces a final output or an exit criterion is met. At a high level, the following operations are present within the agent loop:

- Assemble context (user request + relevant memory + tool json schemas).

- Call the model (plan, decide next action).

- Take actions (tools, search, code execution, database queries).

- Observe results (tool outputs, errors, intermediate artifacts).

- Update memory (write transcripts, store artifacts, summarize, index).

- Repeat until the task completes or hands control back to the user.

Anthropic’s guidance on long-running agents directly points to this: they describe harness practices that help agents quickly re-understand the state of work when starting with a fresh context window, including maintaining explicit progress artifacts.

The agent harness is the surrounding runtime and rules that make the loop reliable: how you wire tools, where you write artifacts, how you log/trace behavior, how you manage memory, and how you prevent the agent from drowning in context.

To complete the picture, the discipline of context engineering is heavily involved in the agent loop and aspect of the agent harness itself. Context engineering is the systematic design and curation of the content placed in an LLM’s context window so that the model receives high-signal tokens and produces the intended, reliable output within a fixed budget.

In this piece, we implement context engineering as a set of repeatable techniques inside the agent harness:

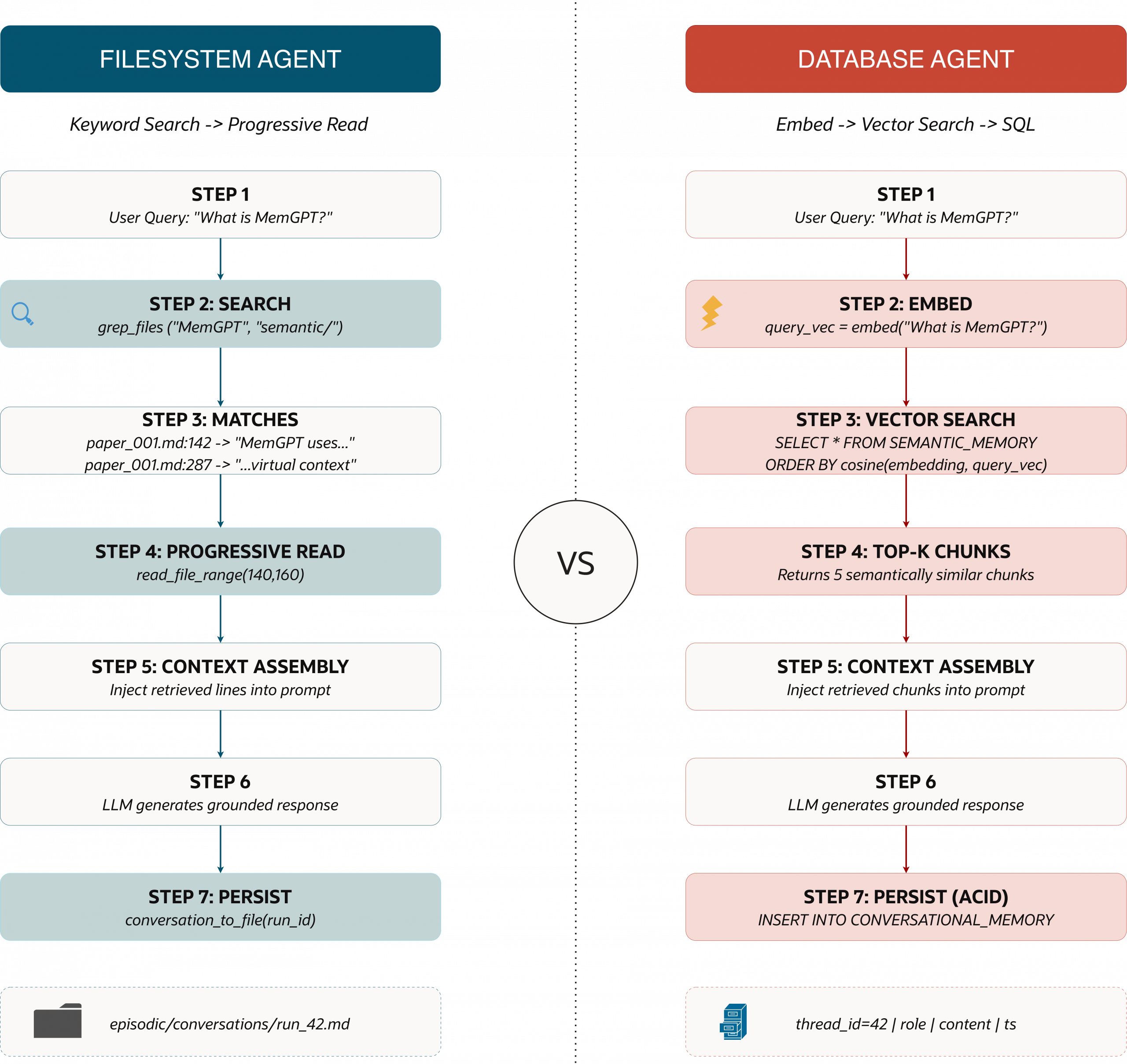

- Context retrieval and selection: Pull only what is relevant (via grep for filesystem memory, via vector similarity and SQL filters for database memory).

- Progressive disclosure: Start small (snippets, tails, line ranges) and expand only when needed.

- Context offloading: Write large tool outputs and artifacts outside the prompt, then reload selectively.

- Context reduction: Summarize or compact information when you approach a degradation threshold, then store the summary in durable memory so you can rehydrate later.

The concepts and explanations above set us up for the rest of the comparison we introduce in this piece. Now that we have the “why” and the moving parts (stateless models, the agent loop, the agent harness, and memory), we can evaluate the two dominant substrates teams are using today to make memory real: the filesystem and the database.

Filesystem-first Agentic Research Assistant

A filesystem-based memory architecture is not “the agent remembers everything forever”. It is the agent that can persist state and artifacts outside the context window and then pull them back selectively when needed. This aligns with two of the earlier-mentioned LLM constraints: a limited context window and statelessness.

In our Research Assistant, the filesystem becomes the memory substrate. Rather than injecting a large number of tools and extensive documentation into the LLM’s context window (which would inflate the token count and trigger early summarization), we store them on disk and let the agent search and selectively read what it needs. This matches with what the Applied AI team at Cursor calls “Dynamic Context Discovery”: write large output to files, then let the agent tail and read ranges as required.

Our FSAgent and demo is using valid filesystem-OS related operations (such as tail and cat to read the contents of files; but that this is a very “simplified” approach, with a limited number of operations for demonstration purposes, and the capabilities offered in the file system can be optimized (with other commands and implementations).

On the other hand, it’s a great start for people to get familiarized with tool access and how file system memory is achieved.

- Semantic memory (durable knowledge): papers and reference docs saved as markdown.

- Episodic memory (experience): conversation transcripts + tool outputs per session/run.

- Procedural memory (how to work): “rules” / instructions files (e.g., CLAUDE.md / AGENTS.md) that shape behavior across sessions.

What does this look like in tooling?

Before we jump into the code, here’s the minimal tool surface we provide to the agent in the table below. Notice the pattern: instead of inventing specialized “memory APIs,” we expose a small set of filesystem primitives and let the agent compose them (very Unix).

| Tool | What it does | Output |

| arxiv_search_candidates(query, k=5) | Searches arXiv and returns a JSON list of candidate papers with IDs, titles, authors, and abstracts. | JSON string of paper candidates |

| fetch_and_save_paper(arxiv_id) | Fetches full paper text (PDF → text) and saves to semantic/knowledge_base/<id>.md Avoids routing full content through the LLM. | File path |

| read_file(path) | Reads a file from disk and returns its contents in full (use sparingly). | Full file contents |

| tail_file(path, n_lines=80) | Reads the last N lines of a file (first step for large files). | Last N lines |

| read_file_range(path, start_line, end_line) | Reads a line range to “zoom in” without loading everything. | Selected line range |

| grep_files(pattern, root_dir, file_glob) | Grep-like search across files to find relevant passages quickly. | Matches with file path + line number |

| list_papers() | Lists all locally saved papers in semantic/knowledge_base/ | List of filenames |

| conversation_to_file(run_id, messages) | Appends conversation entries to one transcript file per run in episodic/conversations/ | File path |

| summarise_conversation_to_file(run_id, messages) | Saves full transcript, then writes a compact summary to episodic/summaries/ | Dict with transcript + summary paths |

| monitor_context_window(messages) | Estimates current context usage (tokens used/remaining). | Dict with token stats |

This design directly reflects what the AI ecosystem is converging on: a filesystem and a handful of core tools, rather than an explosion of bespoke tools.

Progressive reading (read, tail, range)

The first memory principle implementation is simple: don’t load large files unless you must. Filesystems are excellent at sequential read/write and work naturally with tools like grep and log-style access. This makes them a strong fit for append-only transcript and artifact storage.

That’s why we implement three reading tools:

- Read everything (rare),

- Read the end (common for logs/transcripts)

- Read a slice (common for zooming into a match)

The tools below were implemented in Python and converted into objects callable by a langchain agent using the @tool decorator from the langchain agent module.

First is the read_file tool, the “load it all” option. This tool is useful when the file is small, or you truly need the full artifact, but it’s intentionally not the default because it can expand the context window.

@tool

def read_file(path: str) -> str:

p = Path(path)

if not p.exists():

return f"File not found: {path}"

return p.read_text(encoding="utf-8")The tail_file function is the first step for large files. It grabs the end of a log/transcript to quickly see the latest or most relevant portion before deciding whether to read more.

@tool

def tail_file(path: str, n_lines: int = 80) -> str:

p = Path(path)

if not p.exists():

return f"File not found: {path}"

lines = p.read_text(encoding="utf-8").splitlines()

return "\n".join(lines[-max(1, n_lines):])The read_file_range function is seen as the surgical tool that is used once you’ve located the right region (often via grep or after a tail), pulls in just the exact line span you need, so the agent stays token-efficient and grounded.

@tool

def read_file_range(path: str, start_line: int, end_line: int) -> str:

p = Path(path)

if not p.exists():

return f"File not found: {path}"

lines = p.read_text(encoding="utf-8").splitlines()

start = max(0, start_line)

end = min(len(lines), end_line)

if start >= end:

return f"Empty range: {start_line}:{end_line} (file has {len(lines)} lines)"

return "\n".join(lines[start:end])Again, this is essentially dynamic context discovery in a microcosm: load a small view first, then expand only when needed.

Grep-style search (find first, read second)

A filesystem-based agent should quickly find relevant material and pull only the exact slices it needs. This is why grep is such a recurring theme in the agent tooling conversation: it gives the model a fast way to locate relevant regions before spending tokens to pull content.

Here’s a simple grep-like tool that returns line-numbered hits so the agent can immediately jump to read_file_range:

@tool

def grep_files(

pattern: str,

root_dir: str = "semantic",

file_glob: str = "**/*.md",

max_matches: int = 200,

ignore_case: bool = True,

) -> str:

root = Path(root_dir)

if not root.exists():

return f"Directory not found: {root_dir}"

flags = re.IGNORECASE if ignore_case else 0

try:

rx = re.compile(pattern, flags)

except re.error as e:

return f"Invalid regex pattern: {e}"

matches = []

for fp in root.glob(file_glob):

if not fp.is_file():

continue

try:

with open(fp, 'r', encoding='utf-8', errors='ignore') as f:

for i, line in enumerate(f, start=1):

if rx.search(line):

matches.append(f"{fp.as_posix()}:{i}: {line.strip()}")

if len(matches) >= max_matches:

return "\n".join(matches) + "\n\n[TRUNCATED: max_matches reached]"

except Exception:

continue

if not matches:

return "No matches found."

return "\n".join(matches)One subtle but important detail in our grep_files implementation is how we read files. Rather than loading entire files into memory with read_text().splitlines(), we iterate lazily with for line in open(fp), which streams one line at a time and keeps memory usage constant regardless of file size.

This aligns with the “find first, read second” philosophy: locate what you need without loading everything upfront. For readers interested in maximum performance, the full notebook also includes a grep_files_os_based variant that shells out to ripgrep or grep, leveraging OS-level optimizations like memory-mapped I/O and SIMD instructions. In practice, this pattern (“search first, then read a range”) is one reason filesystem agents can feel surprisingly strong on focused corpora: the agent iteratively narrows the context instead of relying on a single-shot retrieval query.

Tool outputs as files: keeping big JSON out of the prompt

One of the fastest ways to blow up your context window is to return large JSON payloads from tools. Cursor’s approach is to write these results to files and let the agent inspect them on demand (often starting with tail).

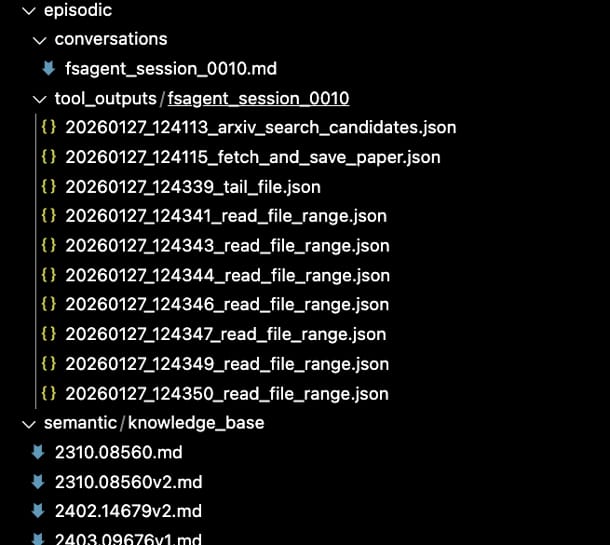

That’s exactly why our folder structure includes a tool_outputs/<session_id>/ directory: it acts like an “evidence locker” for everything the agent did, without forcing those payloads into the current context.

{

"ts_utc": "2026-01-27T12:41:12.135396+00:00",

"tool": "arxiv_search_candidates",

"input": "{'query': 'memgpt'}",

"output": "content='[\\n {\\n \"arxiv_id\": \"2310.08560v2\",\\n \"entry_id\": \"http://arxiv.org/abs/2310.08560v2\",\\n \"title\": \"MemGPT: Towards LLMs as Operating Systems\",\\n \"authors\": \"Charles Packer, Sarah Wooders, Kevin Lin, Vivian Fang, Shishir G. Patil, Ion Stoica, Joseph E. Gonzalez\",\\n \"published\": \"2024-02-12\",\\n \"abstract\": ...msPnaMxOl8Pa'"

}Putting it together: the agent toolset

Before we create the agent, we bundle the tools into a small, composable toolbox. This matches the broader trend: agents often perform better with a smaller tool surface, less choice paralysis (aka context confusion), fewer weird and overlapping tool schemas, and more reliance on proven filesystem workflows.

FS_TOOLS = [

arxiv_search_candidates, # search arXiv for relevant research papers

fetch_and_save_paper, # fetch paper text (PDF->text) and save to semantic/knowledge_base/<id>.md

read_file, # read a file in full (use sparingly)

tail_file, # read end of file first

read_file_range, # read a specific line range

conversation_to_file, # append conversation entries to episodic memory

summarise_conversation_to_file, # save transcript + compact summary

monitor_context_window, # estimate token usage

list_papers, # list saved papers

grep_files # grep-like search over files

]The “filesystem-first” system prompt: policy beats cleverness

Filesystem tools alone aren’t enough—you also need a reading policy that keeps the agent’s token usage efficient and grounded. This is the same reason CLAUDE.md / AGENTS.md/ SKILLS.md, and the “rules files” matter: they’re procedural memory that is applied consistently across sessions.

Key policies we encode below:

- Store big artifacts on disk (papers, tool outputs, transcripts).

- Prefer grep + range reads over full reads.

- Use tail first for large files and logs.

- Be explicit about what you actually read (grounding).

Below is the implementation of an agent using the langchain framework.

fs_agent = create_agent(

model=f"openai:{os.getenv('OPENAI_MODEL', 'gpt-4o-mini')}",

tools=FS_TOOLS,

system_prompt=(

"You are a conversational research ingestion agent.\n\n"

"Core behavior:\n"

"- When asked to find a paper: use arxiv_search_candidates, pick the best arxiv_id, "

"then call fetch_and_save_paper to store the full text in semantic/knowledge_base/.\n"

"- Papers/knowledge base live in semantic/knowledge_base/.\n"

"- Conversations (transcripts) live in episodic/conversations/ (one file per run).\n"

"- Summaries live in episodic/summaries/.\n"

"- Conversation may be summarised externally; respect summary + transcript references.\n"

),

)What the memory footprint looks like on disk

After running the agent, you end up with a directory layout that makes the agent’s “memory” tangible and inspectable. In your example, the agent produces:

episodic/conversations/fsagent_session_0010.md— the session transcript (episodic memory)episodic/tool_outputs/fsagent_session_0010/*.json— tool results saved as files (evidence + replay)semantic/knowledge_base/*.md— saved papers (semantic memory)

That is exactly the point of filesystem-first memory: the model doesn’t “remember” by magically retaining state; it “remembers” because it can re-open, search, and selectively read its prior artifacts.

This is also why so many teams keep rediscovering the same pattern: files are a simple abstraction, and agents are surprisingly good at using them.

Advantages of File Systems In AI Agents

In the previous section, we showed what a filesystem‑first memory harness looks like in practice: the agent writes durable artifacts (papers, tool outputs, transcripts) to disk, then “remembers” by searching and selectively reading only the parts it needs.

This approach works because it directly addresses two core constraints of LLMs: limited context windows and inherent statelessness. Once those constraints are handled, it becomes clear why file systems so often become the default interface for early agent systems.

- Pretraining‑native interface: LLMs have ingested massive amounts of repos, docs, logs, and README‑driven workflows, so folders and files are a familiar operating surface.

- Simple primitives, strong composition: A small action set (list/read/write/search) composes into sophisticated behavior without needing schemas, migrations, or query planning.

- Token efficiency via progressive disclosure: Retrieve via search, then load a small slice (snippets, line ranges) instead of dumping entire documents into the prompt.

- Natural home for artifacts and evidence: Transcripts, intermediate results, cached documents, and tool outputs fit cleanly as files and remain human‑inspectable.

- Debuggable by default: You can open the directory and see exactly what the agent saved, what tools returned, and what the agent could have referenced.

- Portability: A folder is easy to copy, zip, diff, version, and replay elsewhere—great for demos, reproducibility, and handoffs.

- Low operational overhead: For PoCs and MVPs, you get persistence and structure without provisioning extra infrastructure.

In practice, filesystem memory excels when the workload is artifact‑heavy (research notes, paper dumps, transcripts), when you want a clear audit trail, and when iteration speed matters more than sophisticated retrieval. It also encourages good agent hygiene: write outputs down, cite sources, and load only what you need.

Disadvantages of Filesystems In AI Agents

But, unfortunately, it doesn’t end there. The same strengths that make files attractive, simplicity, relatively low cost, and fast implementation, can quickly become bottlenecks once you promote these systems into production, where they are expected to behave like a shared, reliable memory platform.

As soon as an agent moves beyond single-user prototypes into real-world scenarios, where concurrent reads and writes are the norm and robustness under load is non-negotiable, filesystems start to show their limits.

- Weak concurrency guarantees by default: Multiple processes can overwrite or interleave writes unless you implement locking correctly. Even then, locking semantics vary across platforms and network filesystems.

- No ACID transactions: You don’t get atomic multi-step updates, isolation between writers, or durable commit semantics without building them. Partial writes and mid-operation failures can leave memory in inconsistent states.

- Search quality is usually brittle: Keyword/grep-style retrieval misses meaning, synonyms, and paraphrases.

- Scaling becomes “death by a thousand files”: Directory bloat, fragmented artifacts, and expensive scans make performance degrade as memory grows, especially if you rely on repeated full-folder searches.

- Indexing is DIY: The moment you want fast retrieval, deduplication, ranking, or recency weighting, you end up maintaining your own indexes and metadata stores (which, being honest here…is basically a database).

- Metadata and schema drift: Agents inevitably accumulate extra fields (source URLs, timestamps, embeddings, tags). Keeping those consistent across files is harder than enforcing constraints in tables.

- Poor multi-user / multi-agent coordination: Shared memory across agents means shared state. Without a central coordinator, you’ll hit race conditions, inconsistent views, and an unclear “source of truth.”

- Harder auditing at scale: Files are human-readable, but reconstructing “what happened” across many runs and threads becomes messy without structured logs, timestamps, and queryable history.

- Security and access control are coarse: Permissions are filesystem-level, not row-level. It’s hard to enforce “agent A can read X but not Y” without duplicating data or adding an auth layer.

The core pattern is that filesystem memory stays attractive until you need correctness under concurrency, semantic retrieval, or structured guarantees. At that point, you either accept the limitations (and keep the agent single-user/single-process) or you adopt a database.

Database For Agent Memory

By this point, most AI developers can see why filesystem first agent implementations are having a moment. It is a familiar interface, easy to prototype with, and our agents can “remember” by writing artifacts to disk and reloading them later via search plus selective reads. For a single developer on a laptop, that is often enough. But once we move beyond “it works on my laptop” and start supporting developers who ship to thousands or millions of users, memory stops being a folder of helpful files and becomes a shared system that has to behave predictably under load.

Databases were created for the exact moment when “a pile of files” stops being good enough because too many people and processes are touching the same data. One of the most-cited origin stories of the database dates to the Apollo era. IBM, alongside partners, built what became IMS to manage complex operational data for the program, and early versions were installed in 1968 at the Rockwell Space Division, supporting NASA. The point was not simply storage. It was coordination, correctness, and the ability to trust shared data while many activities were happening simultaneously.

That same production reality is what pushes agent memory toward databases today.

When agent memory must handle concurrent reads and writes, preserve an auditable history of what happened, support fast retrieval across many sessions, and enforce consistent updates, we want database guarantees rather than best-effort file conventions.

Oracle has been solving these exact problems since 1979, when we shipped the first commercial SQL database. The goal then was the same as now: make shared state reliable, portable, and trustworthy under load.

On that note, allow us to show how this can work in practice.

Database-first Research Assistant

In the filesystem first section, our Research Assistant “remembered” by writing artifacts to disk and reloading them later using cheap search plus selective reads. That is a great starting point. But when we want memory that is shared, queryable, and reliable under concurrent use, we need a different foundation.

In this iteration of our agent, we keep the same user experience and the same high-level job. Search arXiv, ingest papers, answer follow-up questions, and maintain continuity across sessions. The difference is that memory now lives in the Oracle AI Database, where we can make it durable, indexed, filterable, and safe for concurrent reads and writes. We also achieve a clean separation between two memory surfaces: structured history in SQL tables and semantic recall via vector search.

The result is what we call a MemAgent, an agent whose memory is not a folder of artifacts, but a queryable system. It is designed to support multi-threaded sessions, store full conversational history, store tool logs for debugging and auditing, and store a semantic knowledge base that can be searched by meaning rather than keywords.

Available tools for MemAgent

Before we wire up the agent loop, we need to define the tool surface that MemAgent can use to reason, retrieve, and persist knowledge. The design goal here is similar to the filesystem-first approach: keep the toolset small and composable, but shift the memory substrate from files to the database. Instead of grepping folders and reading line ranges, MemAgent uses vector similarity search to retrieve semantically relevant context, and it persists what it learns in a way that is queryable and reliable across sessions.

In practice, that means two things.

- First, ingestion tools do not just “fetch” content; they also chunk and embed it so it becomes searchable later.

- Second, retrieval tools are meaning-based rather than keyword-based, so the agent can find relevant passages even when the user paraphrases, uses synonyms, or asks higher-level conceptual questions.

The table below summarizes the minimal set of tools we expose to MemAgent and where each tool stores its outputs.

| Tool | What it does |

| arxiv_search_candidates(query, k) | Searches arXiv for candidate papers |

| fetch_and_save_paper_to_kb_db(arxiv_id) | Fetches paper, chunks text, stores embeddings |

| search_knowledge_base(query, k) | Semantic search over stored papers |

| store_to_knowledge_base(text, metadata) | Manually store text with metadata |

FSAgent and MemAgent can look similar from the outside because both can ingest papers, answer questions, and maintain continuity. The difference is what powers that continuity and how retrieval works when the system grows.

FSAgent relies on the operating system as its memory surface, which is great for iteration speed and human inspectability, but it typically relies on keyword-style discovery and file traversal. MemAgent treats memory as a database concern, which adds setup overhead, but unlocks indexed retrieval, stronger guarantees under concurrency, and richer ways to query and filter what the agent has learned.

| Aspect | FSAgent (Filesystem) | MemAgent (Database) |

| Search | Keyword and grep | Semantic similarity |

| Persistence | Markdown files | SQL tables + vector indexes |

| Scalability | Directory traversal | Indexed queries |

| Query Language | Paths and regex | SQL + vector similarity |

| Setup Complexity | Minimal | Requires database runtime |

Creating data stores with LangChain and Oracle AI Database

Before we start defining tables and vector stores, it is worth being explicit about the stack we are using and why. In this implementation, we are not building a bespoke agent framework from scratch.

We use LangChain as the LLM framework to abstract the agent loop, tool calling, and message handling, then pair it with a model provider for reasoning and generation, and with Oracle AI Database as the unified memory core that stores both structured history and semantic embeddings.

This separation is important because it mirrors how production agent systems are typically built. The agent logic evolves quickly, the model can be swapped, and the memory layer must remain reliable and queryable.

Think of this as the agent stack. Each layer has a clear job, and together they create an agent that is both practical to build and robust enough to scale.

- Model provider (OpenAI): generates reasoning, responses, and tool decisions.

- LLM framework (LangChain): provides the agent abstraction, tool wiring, and runtime orchestration.

- Unified memory core (Oracle AI Database): stores durable conversational memory in SQL and semantic memory in vector indexes.

With that stack in place, the first step is simply to connect to the Oracle Database and initialize an embedding model. The database connection serves as the foundation for all memory operations, and the embedding model enables us to store and retrieve knowledge semantically through the vector store layer.

def connect_oracle(user, password, dsn="127.0.0.1:1521/FREEPDB1", program="langchain_oracledb_demo"):

return oracledb.connect(user=user, password=password, dsn=dsn, program=program)

database_connection = connect_oracle(

user="VECTOR",

password="VectorPwd_2025",

dsn="127.0.0.1:1521/FREEPDB1",

program="devrel.content.filesystem_vs_dbs",

)

print("Using user:", database_connection.username)

embedding_model = HuggingFaceEmbeddings(

model_name="sentence-transformers/paraphrase-mpnet-base-v2"

)Next, we define the database schema to store our agent’s memory and prepare a clean slate for the demo. We separate memory into distinct tables so each type can be managed, indexed, and queried appropriately.

Installing the Oracle Database integration in the LangChain ecosystem is straightforward. You can add it to your environment with a single pip command:

pip install -U langchain-oracledb

Conversational history and logs are naturally tabular, while semantic and summary memory are stored in vector-backed tables through OracleVS. For reproducibility, we drop any existing tables from previous runs, making the notebook deterministic and avoiding confusing results when you re-run the walkthrough.

from langchain_oracledb.vectorstores import OracleVS

from langchain_oracledb.vectorstores.oraclevs import create_index

from langchain_community.vectorstores.utils import DistanceStrategy

CONVERSATIONAL_TABLE = "CONVERSATIONAL_MEMORY"

KNOWLEDGE_BASE_TABLE = "SEMANTIC_MEMORY"

LOGS_TABLE = "LOGS_MEMORY"

SUMMARY_TABLE = "SUMMARY_MEMORY"

ALL_TABLES = [

CONVERSATIONAL_TABLE,

KNOWLEDGE_BASE_TABLE,

LOGS_TABLE,

SUMMARY_TABLE

]

for table in ALL_TABLES:

try:

with database_connection.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(f"DROP TABLE {table} PURGE")

except Exception as e:

if "ORA-00942" in str(e):

print(f" - {table} (not exists)")

else:

print(f" [FAIL] {table}: {e}")

database_connection.commit()

Create the vector stores and HNSW indexes

For this section, it is worth explaining what a “vector store” actually is in the context of agents. A vector store is a storage system that persists embeddings alongside metadata and supports similarity search, so the agent can retrieve items by meaning rather than keywords.

Instead of asking “which file contains this exact phrase”, the agent asks “which chunks are semantically closest to my question” and pulls back the best matches.

Under the hood, that usually means an approximate nearest neighbor index, because scanning every vector becomes prohibitively expensive as your knowledge base grows. HNSW is one of the most common indexing approaches for this style of retrieval.

In the code below, we create two vector stores using the langchain_oracledb module OracleVS, one for the knowledge base and one for summaries, both using cosine distance.

Second, it builds HNSW indexes so similarity search stays fast as memory grows, which is exactly what you want once your Research Assistant starts ingesting many papers and running over long-lived threads.

knowledge_base_vs = OracleVS(

client=database_connection,

embedding_function=embedding_model,

table_name=KNOWLEDGE_BASE_TABLE,

distance_strategy=DistanceStrategy.COSINE,

)

summary_vs = OracleVS(

client=database_connection,

embedding_function=embedding_model,

table_name=SUMMARY_TABLE,

distance_strategy=DistanceStrategy.COSINE,

)

def safe_create_index(conn, vs, idx_name):

try:

create_index(

client=conn,

vector_store=vs,

params={"idx_name": idx_name, "idx_type": "HNSW"}

)

print(f" Created index: {idx_name}")

except Exception as e:

if "ORA-00955" in str(e):

print(f" [SKIP] Index already exists: {idx_name}")

else:

raise

print("Creating vector indexes...")

safe_create_index(database_connection, knowledge_base_vs, "kb_hnsw_cosine_idx")

safe_create_index(database_connection, summary_vs, "summary_hnsw_cosine_idx")

print("All indexes created!")

Memory Manager

In the code below, we create a custom Memory manager. The Memory manager is the abstraction layer that turns raw database operations into “agent memory behaviours”. This is the part that makes the database-first agent easy to reason about.

- SQL methods store and load conversational history by

thread_id - Vector methods store and retrieve semantic memory by similarity search

- Summary methods store compressed context and let us rotate the working set when we approach context limits

from langchain.tools import tool

from typing import List, Dict

class MemoryManager:

"""

A simplified memory manager for AI agents using Oracle AI Database.

"""

def __init__(self, conn, conversation_table: str, knowledge_base_vs, summary_vs, tool_log_table):

self.conn = conn

self.conversation_table = conversation_table

self.knowledge_base_vs = knowledge_base_vs

self.summary_vs = summary_vs

self.tool_log_table = tool_log_table

def write_conversational_memory(self, content: str, role: str, thread_id: str) -> str:

thread_id = str(thread_id)

with self.conn.cursor() as cur:

id_var = cur.var(str)

cur.execute(f"""

INSERT INTO {self.conversation_table} (thread_id, role, content, metadata, timestamp)

VALUES (:thread_id, :role, :content, :metadata, CURRENT_TIMESTAMP)

RETURNING id INTO :id

""", {"thread_id": thread_id, "role": role, "content": content, "metadata": "{}", "id": id_var})

record_id = id_var.getvalue()[0] if id_var.getvalue() else None

self.conn.commit()

return record_id

def load_conversational_history(self, thread_id: str, limit: int = 50) -> List[Dict[str, str]]:

thread_id = str(thread_id)

with self.conn.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(f"""

SELECT role, content FROM {self.conversation_table}

WHERE thread_id = :thread_id AND summary_id IS NULL

ORDER BY timestamp ASC

FETCH FIRST :limit ROWS ONLY

""", {"thread_id": thread_id, "limit": limit})

results = cur.fetchall()

return [{"role": str(role), "content": content.read() if hasattr(content, 'read') else str(content)} for role, content in results]

def mark_as_summarized(self, thread_id: str, summary_id: str):

thread_id = str(thread_id)

with self.conn.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(f"""

UPDATE {self.conversation_table}

SET summary_id = :summary_id

WHERE thread_id = :thread_id AND summary_id IS NULL

""", {"summary_id": summary_id, "thread_id": thread_id})

self.conn.commit()

print(f" Marked messages as summarized (summary_id: {summary_id})")

def write_knowledge_base(self, text: str, metadata_json: str = "{}"):

metadata = json.loads(metadata_json)

self.knowledge_base_vs.add_texts([text], [metadata])

def read_knowledge_base(self, query: str, k: int = 5) -> str:

results = self.knowledge_base_vs.similarity_search(query, k=k)

content = "\n".join([doc.page_content for doc in results])

return f"""## Knowledge Base Memory: This are general information that is relevant to the question

### How to use: Use the knowledge base as background information that can help answer the question

{content}"""

def write_summary(self, summary_id: str, full_content: str, summary: str, description: str):

self.summary_vs.add_texts(

[f"{summary_id}: {description}"],

[{"id": summary_id, "full_content": full_content, "summary": summary, "description": description}]

)

return summary_id

def read_summary_memory(self, summary_id: str) -> str:

results = self.summary_vs.similarity_search(

summary_id,

k=5,

filter={"id": summary_id}

)

if not results:

return f"Summary {summary_id} not found."

doc = results[0]

return doc.metadata.get('summary', 'No summary content.')

def read_summary_context(self, query: str = "", k: int = 5) -> str:

results = self.summary_vs.similarity_search(query or "summary", k=k)

if not results:

return "## Summary Memory\nNo summaries available."

lines = ["## Summary Memory", "Use expand_summary(id) to get full content:"]

for doc in results:

sid = doc.metadata.get('id', '?')

desc = doc.metadata.get('description', 'No description')

lines.append(f" - [ID: {sid}] {desc}")

return "\n".join(lines)

Then we instantiate it:

memory_manager = MemoryManager(

conn=database_connection,

conversation_table=CONVERSATION_HISTORY_TABLE,

knowledge_base_vs=knowledge_base_vs,

tool_log_table=TOOL_LOG_TABLE,

summary_vs=summary_vs

)Creating the tools and agent

The database-first agent follows a simple, production-friendly pattern.

- Persists every conversation turn as structured rows, including user and assistant messages with thread or run IDs and timestamps, so sessions are recoverable, traceable, and consistent across restarts.

- Persists long-term knowledge in a vector-enabled store by chunking documents, generating embeddings, and storing them with metadata, so retrieval is semantic, ranked, and fast as the corpus grows.

- Persists tool activity as first-class records that capture the tool name, inputs, outputs, status, errors, and key metadata, so agent behavior is inspectable, reproducible, and auditable.

On top of that, the agent actively manages context: it tracks token usage and periodically rolls older dialogue and intermediate state into durable summaries (and/or “memory” tables), so the working prompt stays small while the full history remains available on demand.

Ingest papers into the knowledge base vector store

This is the database-first equivalent of “fetch and save paper”. Instead of writing markdown files, we do three steps:

- Load paper text from arXiv

- Chunk it to respect the embedding model limits

- Store chunks with metadata in the vector store, which gives us fast semantic search later

from datetime import datetime, timezone

from langchain_core.tools import tool

from langchain_community.document_loaders import ArxivLoader

from langchain_text_splitters import RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter

@tool

def fetch_and_save_paper_to_kb_db(

arxiv_id: str,

chunk_size: int = 1500,

chunk_overlap: int = 200,

) -> str:

loader = ArxivLoader(

query=arxiv_id,

load_max_docs=1,

doc_content_chars_max=None,

)

docs = loader.load()

if not docs:

return f"No documents found for arXiv id: {arxiv_id}"

doc = docs[0]

title = (

doc.metadata.get("Title")

or doc.metadata.get("title")

or f"arXiv {arxiv_id}"

)

entry_id = doc.metadata.get("Entry ID") or doc.metadata.get("entry_id") or ""

published = doc.metadata.get("Published") or doc.metadata.get("published") or ""

authors = doc.metadata.get("Authors") or doc.metadata.get("authors") or ""

full_text = doc.page_content or ""

if not full_text.strip():

return f"Loaded arXiv {arxiv_id} but extracted empty text (PDF parsing issue)."

splitter = RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter(

chunk_size=chunk_size,

chunk_overlap=chunk_overlap,

)

chunks = splitter.split_text(full_text)

ts_utc = datetime.now(timezone.utc).isoformat()

metadatas = []

for i in range(len(chunks)):

metadatas.append(

{

"source": "arxiv",

"arxiv_id": arxiv_id,

"title": title,

"entry_id": entry_id,

"published": str(published),

"authors": str(authors),

"chunk_id": i,

"num_chunks": len(chunks),

"ingested_ts_utc": ts_utc,

}

)

knowledge_base_vs.add_texts(chunks, metadatas)

return (

f"Saved arXiv {arxiv_id} to {KNOWLEDGE_BASE_TABLE}: "

f"{len(chunks)} chunks (title: {title})."

)We create two more tools below:

- search_knowledge_base(query, k=5): Runs a semantic similarity search over the database-backed knowledge base and returns the top k most relevant chunks, so the agent can retrieve context by meaning rather than exact keywords.

- store_to_knowledge_base(text, metadata_json=”{}”): Stores a new piece of text into the knowledge base and attaches metadata (as JSON), which gets embedded and indexed so it becomes searchable in future queries.

import os

from langchain.tools import tool

@tool

def search_knowledge_base(query: str, k: int = 5) -> str:

return memory_manager.read_knowledge_base(query, k)

@tool

def store_to_knowledge_base(text: str, metadata_json: str = "{}") -> str:

memory_manager.write_knowledge_base(text, metadata_json)

return "Successfully stored text to knowledge base."

Now we build the LangChain agent using the database-first tools.

from langchain.agents import create_agent

MEM_AGENT = create_agent(

model=f"openai:{os.getenv('OPENAI_MODEL', 'gpt-4o-mini')}",

tools=[search_knowledge_base, store_to_knowledge_base, arxiv_search_candidates, fetch_and_save_paper_to_kb_db],

)Result Comparison: FSAgent vs MemAgent: End-to-End Benchmark (Latency + Quality)

At this point, the difference between a filesystem agent and a database-backed agent should feel less like a philosophical debate and more like an engineering trade-off. Both approaches can “remember” in the sense that they can persist state, retrieve context, and answer follow-up questions. The real test is what happens when you leave the tidy laptop demo and hit production realities: larger corpora, fuzzier queries, and concurrent workloads.

To make that concrete, we ran an end-to-end benchmark and measured the full agent loop per query—retrieval, context assembly, tool calls, model invocations, and the final answer—across three scenarios:

- Small-corpus retrieval: a tight, keyword-friendly dataset to validate baseline retrieval and answer synthesis with minimal context.

- Large-corpus retrieval: a larger dataset with more paraphrase variability to stress retrieval quality and context efficiency at scale.

- Concurrent write integrity: a multi-worker stress test to evaluate correctness under simultaneous reads/writes (integrity, race conditions, throughput).

FSAgent vs MemAgent: End-to-End Benchmark (Latency + Quality)

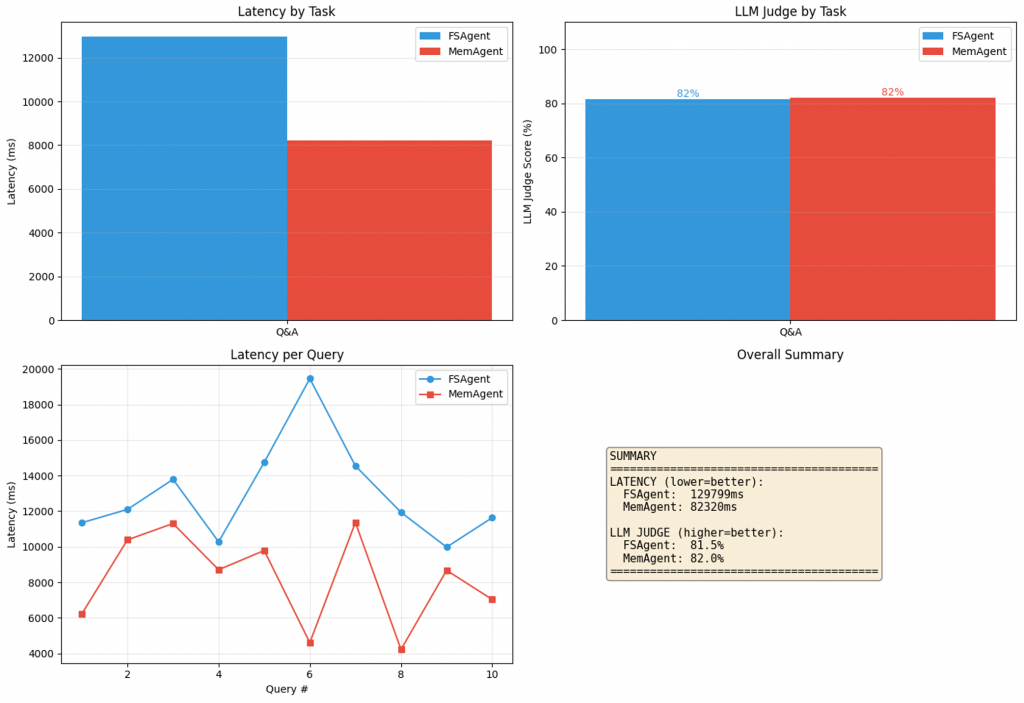

From the result shown in the image above, two conclusions immediately stand out. First, latency and answer quality.

In our run, MemAgent generally finished faster end-to-end than FSAgent. That might sound counterintuitive if you assume “database equals overhead,” and sometimes it does.

But the agent loop is not dominated by raw storage primitives. It is dominated by how quickly you can find the right information and how little unnecessary context you force into the model, also known as context engineering. Semantic retrieval tends to return fewer, more relevant chunks(subject to tuning of the retrieval pipelines), which means less scanning, less paging through files, and fewer tokens burned on irrelevant text.

In this particular run, both agents produced similar-quality answers. That is not surprising. When the questions are retrieval-friendly and the corpus is small enough, both approaches can find the right passages. FSAgent gets there through keyword search and careful reading. MemAgent gets there through similarity search over embedded chunks. Different roads, similar destination.

And I think it’s worth zooming in on one nuance here. When the information to traverse is minimal in terms of character length and the query is keyword-friendly, the retrieval quality of both agents tends to converge. At that scale, “search” is barely a problem, so the dominant factor becomes the model’s ability to read and synthesise, not the retrieval substrate. The gap only starts to widen when the corpus grows, the wording becomes fuzzier, and the system must retrieve reliably under real-world constraints such as noise, paraphrases, and concurrency. Which it eventually does.

About the “LLM-as-a-Judge” metric

We also scored answers using an LLM-as-a-judge prompt. It is a pragmatic way to get directional feedback when you do not have labeled ground truth, but it is not a silver bullet. Judges can be sensitive to prompt phrasing, can over-reward fluency, and can miss subtle grounding failures.

If you are building this for production, treat LLM judging as a starting signal, not the finish line. The more reliable approach is a mix of:

- Reference-based evaluation when you have ground truth, such as rubric grading, exact match, or F1-style scoring.

- Retrieval-aware evaluation when context matters, such as context precision and recall, answer faithfulness, and groundedness.

Tracing plus evaluation tooling so you can connect failures to the specific retrievals, tool calls, and context assembly decisions that caused them.

Even with a lightweight judge, the directional story remains consistent. As retrieval becomes more difficult and the system becomes busier, database-backed memory tends to perform better.

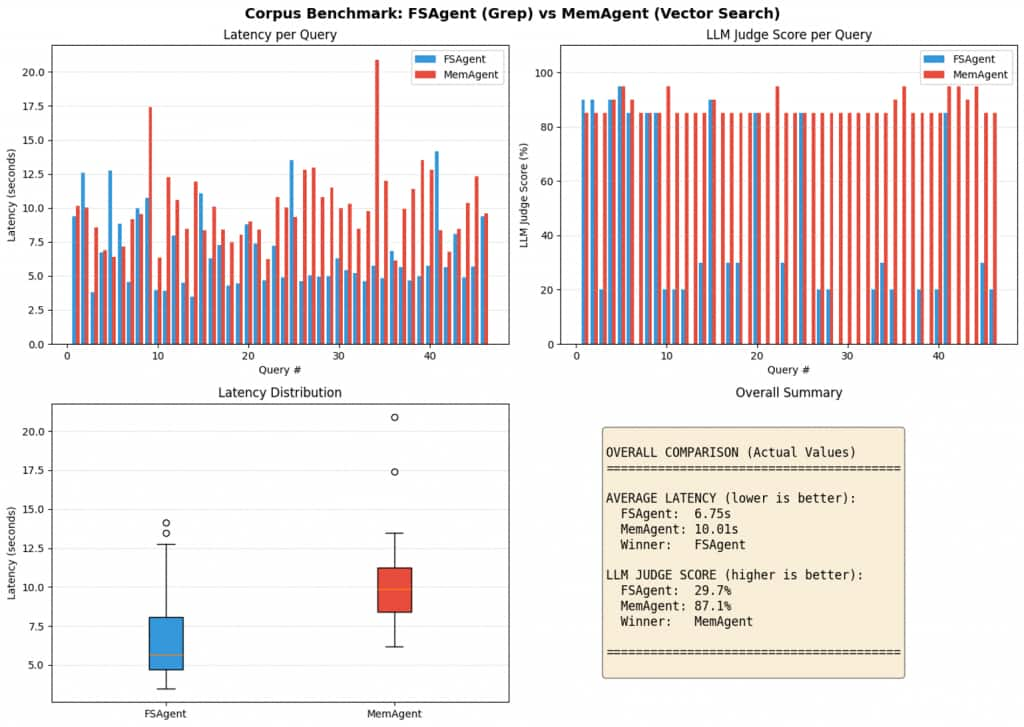

Large Corpus Benchmark: Why the gap widens as data grows

The large-corpus test is designed to stress the exact weakness of keyword-first memory. We intentionally made the search problem harder by growing the corpus and making the queries less “exact match.”

FSAgent with a concatenated corpus:

When you merge many papers into large markdown files, FSAgent becomes dependent on grep-style discovery followed by paging the right sections into the context window. It can work, but it gets brittle as the corpus grows:

- If the user paraphrases or uses synonyms, exact keyword matches can fail.

- If the keyword is too common, you get too many hits, and the agent has to sift through them manually.

- When uncertain, the agent often loads larger slices “just in case,” which increases token count, latency, and the risk of context dilution.

MemAgent with chunked, embedded memory:

Chunking plus embeddings makes retrieval more forgiving and more stable:

- The user does not need to match the source phrasing exactly.

- The agent can fetch a small set of high-similarity chunks, keeping context tight.

- Indexed retrieval remains predictable as memory grows, rather than requiring repeated scans of files.

The narrative takeaway is simple. Filesystems feel great when the corpus is small and the queries are keyword-friendly. As the corpus grows and the questions get fuzzier, semantic retrieval becomes the differentiator, and database-backed memory becomes the more dependable default.

The quality gap widens with scale. On a handful of documents, grep can brute-force its way to a reasonable answer: the agent finds a keyword match, pulls surrounding context, and responds.

But scatter the same information across hundreds of files, and keyword search starts missing the forest for the trees. It returns too many shallow hits or none when the user’s phrasing doesn’t match the source text verbatim. Semantic search, by contrast, surfaces conceptually relevant chunks even when the vocabulary differs. The result isn’t just faster retrieval, it’s more coherent answers with fewer hallucinated gaps. This is evident in our LLM judge evaluation on the large corpus benchmark, where FSAgent achieved a score of 29.7% while MemAgent reached 87.1%.

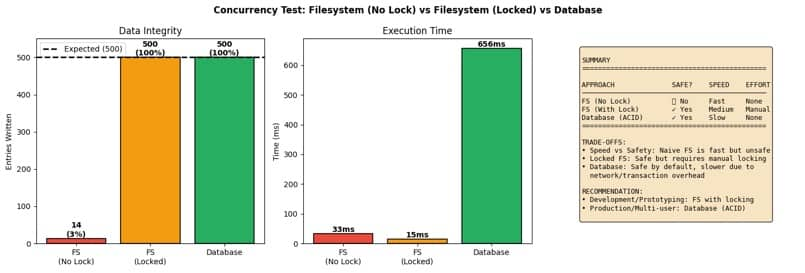

Concurrency Test: What production teaches you very quickly

We find that the real breaking point for filesystem memory is rarely retrieval. It is concurrency.

We ran three versions of the same workload under concurrent writes:

- Filesystem without locking, where multiple workers append to the same file.

- Filesystem with locking, where writes are guarded by file locks.

- Oracle AI Database with transactions, where multiple workers write rows under ACID guarantees.

Then we measured two things:

- Integrity, meaning, did we get the expected number of entries with no corruption?

- Execution time, meaning how long the batch took end-to-end.

What we observed maps to what many teams discover the hard way.

Naive filesystem writes can be fast and still be wrong. Without locking, concurrent writes conflict with each other. You might get good throughput and still lose memory entries. If your agent’s “memory” is used for downstream reasoning, silent loss is not a performance issue. It is a correctness failure.

Locking fixes integrity, but now correctness is your job. With explicit locking, you can make filesystem writes safe. But you inherit the complexity. Lock scope, lock contention, platform differences, network filesystem behavior, and failure recovery all become part of your agent engineering work.

Databases make correctness the default. Transactions and isolation are exactly what databases were designed for. Yes, there is overhead. But the key difference is that you are not bolting correctness on after a production incident. You start with a system whose job is to protect the shared state.

And of course, you can take the file-locking approach, add atomic writes, build a write-ahead log, introduce retry and recovery logic, maintain indexes for fast lookups, and standardise metadata so you can query it reliably.

Eventually, though, you will realise you have not “avoided” a database at all.

You have just rebuilt one, only with fewer guarantees and more edge cases to own.

Conclusion: Is there a happy medium for AI Developers?

This isn’t a religious war between “files” and “databases.” It’s a question of what you’re optimizing for—and which failure modes you’re willing to own. If you’re building single-user or single-writer prototypes, filesystem memory is a great default. It’s simple, transparent, and fast to iterate on. You can open a folder and see exactly what the agent saved, diff it, version it, and replay it with nothing more than a text editor.

If you’re building multi-user agents, background workers, or anything you plan to ship at scale, a database-backed memory store is a safer foundation at that stage. At that stage, concurrency, integrity, governance, access control, and auditability matter more than raw simplicity. A practical compromise is a hybrid design: keep file-like ergonomics for artifacts and developer workflows, but store durable memory in a database that can enforce correctness.

And if you insist on filesystem-only memory in production, treat locking, atomic writes, recovery, indexing, and metadata discipline as first-class engineering work. Because the moment you do that seriously, you’re no longer “just using files”—you’re rebuilding a database.

One last trap worth calling out: polyglot persistence.

Many AI stacks drift into an anti-pattern: a vector DB for embeddings, a NoSQL DB for JSON, a graph DB for relationships, and a relational DB for transactions. Each product is “best at its one thing,” until you realize you’re operating four databases, four security models, four backup strategies, four scaling profiles, and four cascading failure points.

Coordination becomes the tax. You end up building glue code and sync pipelines just to make the system feel unified to the agent. This is why converged approaches matter in agent systems: production memory isn’t only about storing vectors—it’s about storing operational history, artifacts, metadata, and semantics under one consistent set of guarantees.

For AI Developers, your application acts as an integration layer for multiple storage engines, each with different access patterns and operational semantics. You end up building glue code, sync pipelines, and reconciliation logic just to make the system feel unified to the agent.

Of course, production data is inherently heterogeneous. You will inevitably deal with structured, semi-structured, unstructured text, embeddings, JSON documents, and relationship-heavy data.

The point is not that “one model wins”.

The point is that when you understand the fundamentals of data management, reliability, indexing, governance, and queryability, you want a platform that can store and retrieve these forms without turning your AI infrastructure into a collection of loosely coordinated subsystems.

This is the philosophy behind Oracle’s converged database approach, which is designed to support multiple data types and workloads natively within a single engine. In the world of agents, that becomes a practical advantage because we can use Oracle as the unified memory core for both operational memory (SQL tables for history and logs) and semantic memory (vector search for retrieval).

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is AI Agent memory? AI agent memory is the set of system components and techniques that enable an AI agent to store, recall, and update information over time. Because LLMs are inherently stateless—they have no built-in ability to remember previous sessions—agent memory provides the persistence layer that allows agents to maintain continuity across conversations, learn from past interactions, and adapt to user preferences.

- Should I use a filesystem or a database for an AI agent’s memory? It depends on your use case. Filesystems excel at single-user prototypes, artifact-heavy workflows, and rapid iteration—they’re simple, transparent, and align with how LLMs naturally operate. Databases become essential when you need concurrent access, ACID transactions, semantic retrieval, or shared state across multiple agents or users. Many production systems use a hybrid approach: file-like interfaces for agent interaction, with database guarantees underneath.

- How do I build an AI agent with long-term memory? Start by separating memory types: working memory (current context), semantic memory (knowledge base), episodic memory (interaction history), and procedural memory (behavioral rules). Implement storage: a filesystem for prototypes and a database for production. Add retrieval tools that the agent can call. Build a summarization to compress the old context. Test with multi-session scenarios where the agent must recall information from previous conversations.

- What are semantic, episodic, and procedural memory in AI agents? These terms, borrowed from cognitive science, describe different types of agent memory. Semantic memory stores durable knowledge and facts (like saved documents or reference materials). Episodic memory captures experiences and interaction history (conversation transcripts, tool outputs). Procedural memory encodes how the agent should behave—instructions, rules, files like CLAUDE.md, and learned workflows that shape behavior across sessions.

- What is the best database for AI applications? The best database depends on your requirements. For AI agent memory specifically, you need: vector search capability for semantic retrieval, SQL or structured queries for history and metadata, ACID transactions if multiple agents share state, and scalability as your memory corpus grows. Converged databases that combine these capabilities—like Oracle AI Database—reduce operational complexity versus running separate specialized systems.