OCI Policy Analysis was developed to give administrators deep insight into the security posture of their Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI) tenancies. As OCI environments grow in complexity, understanding how IAM policies, dynamic groups, and users interact becomes challenging—especially across many compartments and resource types. Traditional tools often lack holistic policy visibility, historical difference detection, and robust analysis of effective permissions. This project addresses that gap by delivering a cross-platform, graphical solution for actionable policy and identity data analysis.

In this part of the blog, we cover how an idea turned into a script, which turned into a tool. For part 1, which covers the tool itself, see here: Part 1

From Script to Essential Tool

OCI Policy Analysis began as a simple script that pulled all policies from OCI using the official SDK. As the need for more day-to-day utility arose, parsing and filtering of retrieved policies became more apparent. Thus, as part of using the tool daily, new ideas and features went from thoughts to plans, and usability became a central theme. – enabling focused reviews and making the tool valuable for routine operations. Some examples of where this became evident:

- User Interface: At the time the UI was added, the centralized data model had started to be separate from the main script that kicked off the loading process. By “discussing” what the UI options were with the likes of ChatGPT and Claude, it was decided to base it on TKinter, as the most stable and easiest to use for standalone applications. Flet or Flask are still options, but for ease of use, running servers was less desirable.

- Caching: Because it may take several minutes to load data just to check something simple, it makes sense to cache results locally. By storing everything collected during a tenancy load, offline analysis, sharing of data, and reduced API calls were made possible. This evolved into the ability to do a historical comparison of an entire data set with a different point in time.

- Filter Model: As the tool evolved, it became obvious that the data model needed to be further refined, where each type could stand on its own. This helps with filtering both simple and complex types, and became essential for MCP to work properly.

- Advanced Analysis: Once the initial UI elements were in place, the evolution of new tools and ways to look at the same data occurred. For example, by expanding resources out into underlying permission (which are the basis for OCI Security), it was possible to do simulations and understand overlaps.

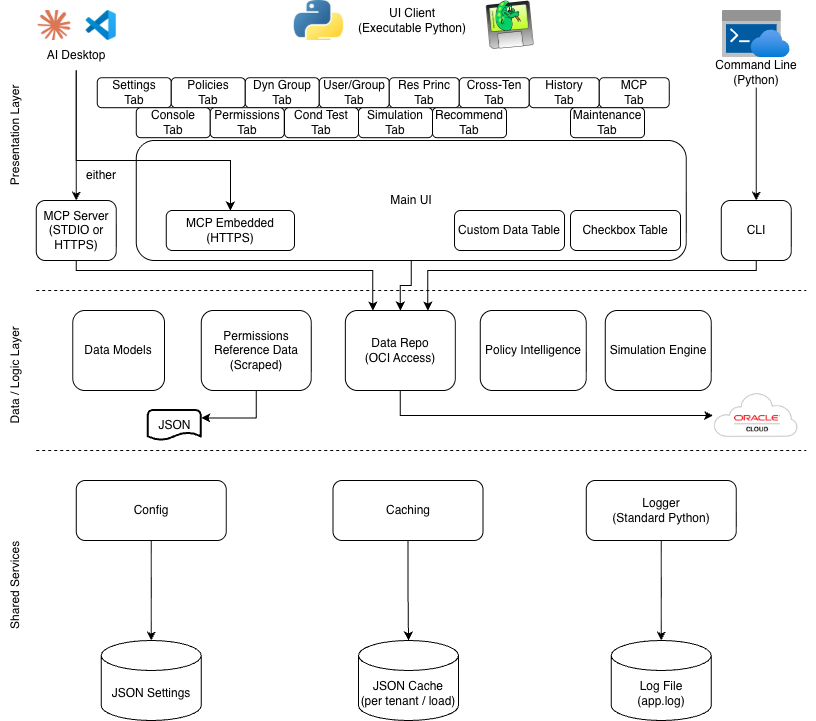

Resulting Architecture

As the project has evolved, I was able to create and maintain an architecture diagram which represents all of the major components, with room to grow. Specifically, the data model and supporting common components (logging, caching, config) are flexible enough to be used throughout future use cases. And the UI components are designed in a way that are independent enough that they can be separately authored as needed.

More enhancements are already planned as of this writing, so as the architecture evolves, the hope is that changes to common or existing components are not necessary.

Reusability, Best Practices, and Ecosystem

To ensure the tool was robust and easy to reuse, it was organized into a formal repository and redesigned to follow modern development best practices. AI was leveraged to help build CI/CD workflows (GitHub Actions), automate semantic versioning, enforce code quality with pre-commit checks, and generate documentation inline for publication to GitHub Pages—all to support a thriving open-source development ecosystem.

This started with a simple GitHub repo, but when executable builds were added, it made sense to implement Actions. Likewise, releases and semantic versioning over time became required to keep up with changes. Tagging and releases fall firmly within the category of good hygiene, so they should be implemented earlier on in a project if it is to become bigger.

Use of AI

Using Oracle Code Assist and Cline, VSCode, and OpenAI Codex at various times helped with multiple aspects – from implementing a standard, cleaning up or re-factoring, organization questions, and just general plan-mode conversation, it can make the code base more stable. There are downsides too, when it comes to complacency. It is imperative to read and approve, fully test, and ask more questions. There are likely more best practices to derive from using AI, such as being specific with changes, asking for context files to be generated (and then use them), and telling it how to document and format code across the code base.

Context Files

One specific means of capturing information before writing code came through as particularly effective in getting larger tasks done. By using the “Plan Mode”, an AI assistant can hold a conversation about a feature or task, and then write a full Markdown-based context file which contains details on what is to be done, UI and backend layout and flow, features to support, relevant files to edit, and more. This context can then be used, along with additional generic context files that contain project-level details, in order to actually build something that is not starting from scratch. One helpful hint is to have AI read, then re-write context files as new changes are introduced. While these files are not being used as documentation yet, they could be adapted into a set format over time, and simply linked into the existing documentation.

Self-Documentation

As part of building something that keeps getting bigger, it was important to realize early that up to date documentation is critical to usability. What good are features that nobody knows about? For this reason, all code in the repository is set up to use Sphinx for documentation, with functions and __init__.py files and the appropriate Sphinx RST files in place. Additionally (thank you ChatGPT), there is a GitHub Actions build file that automatically pushes doc updates to GitHub Pages, where the docs you will read are surfaced.

Lastly, AI helped this effort by suggesting to use, and then providing help with, Mermaid as an in-line markdown-based drawing tool. Rather than creating images and storing them with the documentation, Mermaid gives a nice way to sketch what you are looking to show. After all, a picture is worth 1000 words.

Data Model Meets MCP: Lessons Learned

The enhanced, filterable data model proved to be a great fit for application in Model Context Protocol (MCP) tools. Incorporating MCP support meant tools could provide interactive analysis or summaries to external AI systems or IDE extensions. Important lessons emerged here — such as the need to accommodate MCP content size limits, which led to offering “policy summaries” rather than full content dumps via these interfaces.

As the tool starts to be used more, the expectation is that requests for new MCP tools will be conceived of and built, and maybe one day will be the primary means of accessing the information. This area is still under development, so stay tuned….

Contribution & Future Direction

OCI Policy Analysis already gives users a new perspective on the data they have in their OCI tenancy, showing how the SDK can be leveraged to build powerful custom tools that add value and unlock new ways to visualize and even manipulate cloud assets. Contributions, feedback, and new feature ideas are always welcome—submit them via GitHub Issues to help shape the ongoing direction of the tool. Looking ahead, future releases will focus on enabling more meaningful changes directly from the interface, with an emphasis on improving security posture, reducing unnecessary policies, and supporting better OCI hygiene for organizations of all sizes.

One final thought – if there is enough interest in the overall project, specifically the project, UI structure, AI integration, and tabbed interface, there may be a 3rd part to the blog where a re-usable “OCI custom Application” template can be made available for anyone to use.

This post is part 2 of a two-part series on OCI Policy Analysis. Part 1 covers the tool itself.