I’ve recently started to use secrets and Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI) Vault in more programing as a method to get out of the business of having unsecured, sensitive information floating around. It’s great for storing database information and credentials or email integration information. I even have things like email server address and port stored as secrets because it’s an easy one-stop-shop when I need to pull the credentials. I wouldn’t want to use the vault as a key-value store, but in these isolated cases, it works great.

I recently found myself asking what I would do if a disaster occurred. The bulk of my development is for my own personal education. Nearly all my infrastructure is deployed using some form of scripting, whether Terraform, YAML files for Kubernetes, or cloud-init scripts for the servers. The only thing that really has long-term storage is my MariaDB, and for that, I use backups. I don’t have a good answer for my vaults. That’s not a great situation to be in.

After some research, I discovered that I can replicate and back up vaults using a virtual private vault. Virtual private vault is more than what I need, so I’m left wondering what to do next. Then I decided to write some more code. I’m a Python fan, and the OCI software developer kit (SDK) is slick, so the decision was already made. Time to get started.

I wanted to back up my secrets most urgently. The keys I use aren’t as consequential because I primarily use them for secrets encryption. However, I recognize that backing up your keys is also critical, so the next iteration includes that.

I used the following steps for my backups.

The process

I needed a target vault in another region. Get the list of secrets from the target vault so you can manage updates versus adds. Then get the list of secrets from the source vault. For each secret in the list, get the details and then import it into the target.

Create the target vault and key

To create a vault, I referenced the Vault documentation. Then I created an encryption key for the vault.

Write the code

From there, it was time to code.

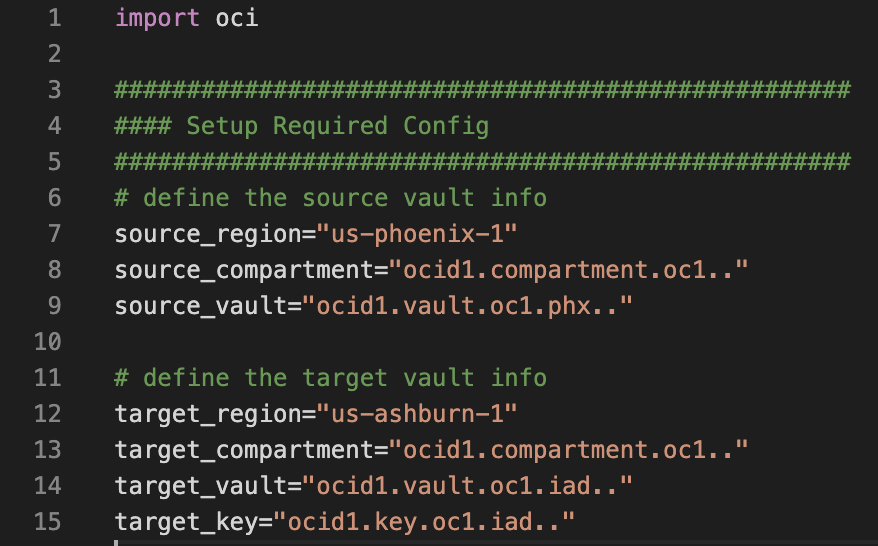

Define the source and target. First, import the OCI module and define the variables you need for later.

We need all this information, including which key you want to use from the target vault to run the encryption when loading to the target vault.

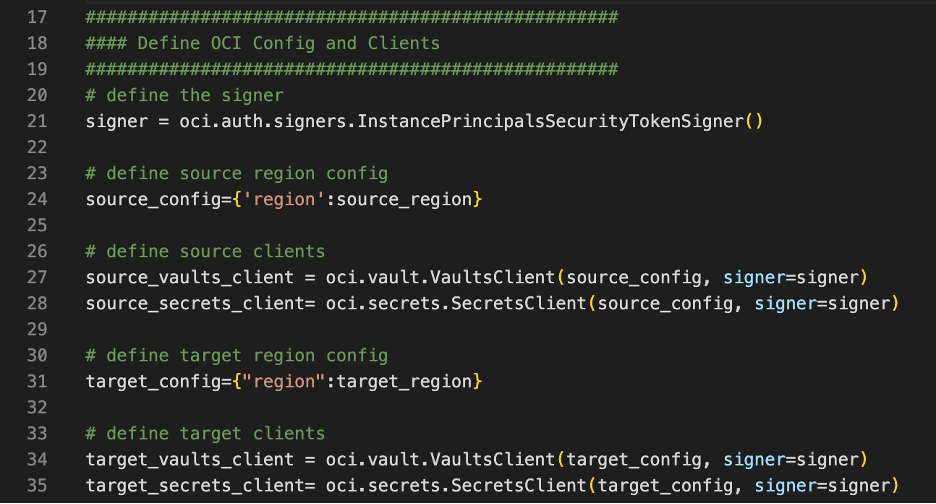

Define the clients. I’m a firm believer in instance principals, so I’m using a signer in all cases. I’m using the region variables that we defined to direct the client to access that region. This way, I define it all one time and move on.

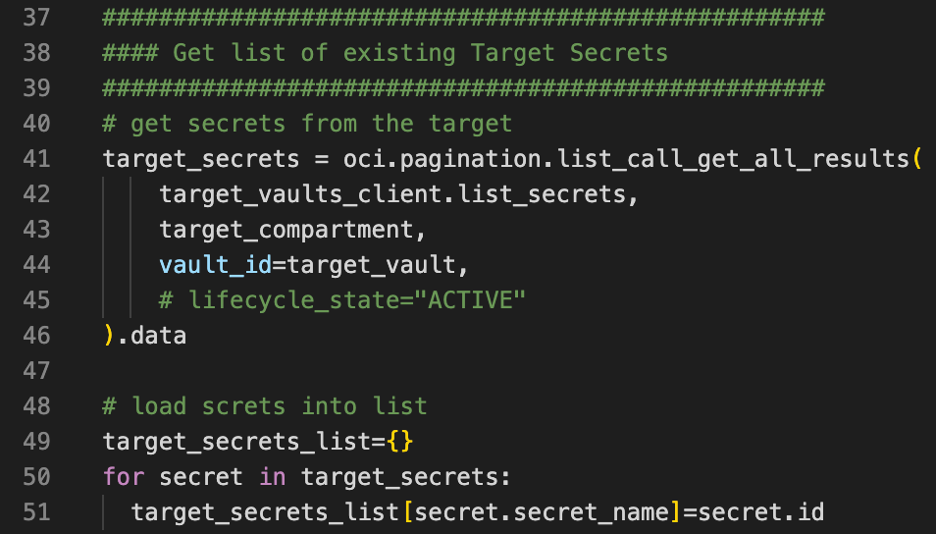

Get the secrets already in the target. If you run this process multiple times, it’s likely that you already have secrets in your target vault and that you’re backing up secrets for the second, third, nth time. If you try to slam your source secrets into the target in this case, you end up with duplication errors.

So, we need to figure out how to update existing secrets that overlap. Secret names must be unique per vault to create a list of secrets in the target vault.

So, we need to figure out how to update existing secrets that overlap. Secret names must be unique per vault to create a list of secrets in the target vault.

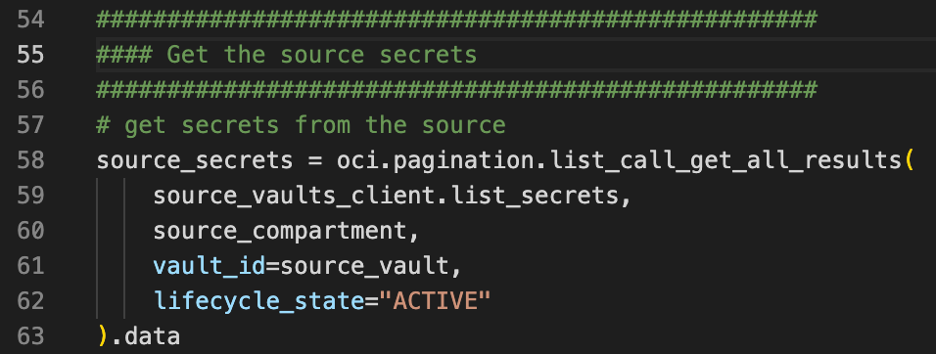

Next, we need to get all the secrets in the source. I only fetch the active secrets for this case.

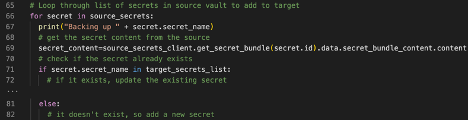

Loop through the source secrets. Now, we need to go through the list of secrets we pulled from the source vault. We need the content of the secret because the content isn’t provided when you list multiple secrets. From there, we check if the secret exists in the target vault. If it does, we need to run an update. If not, we create the secret.

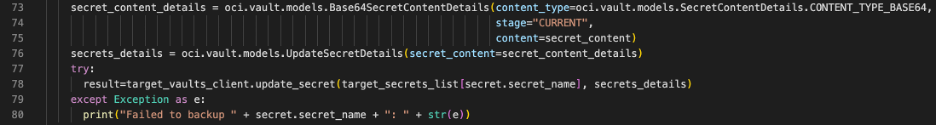

If a secret exists in your target vault, update the existing secret by creating the content details and secret details. You then use the update_secret function with those elements to update the existing secret. Because you defined the dictionary of existing secrets with the name as the key and the OCID as the value, you can get the secret OCID quickly.

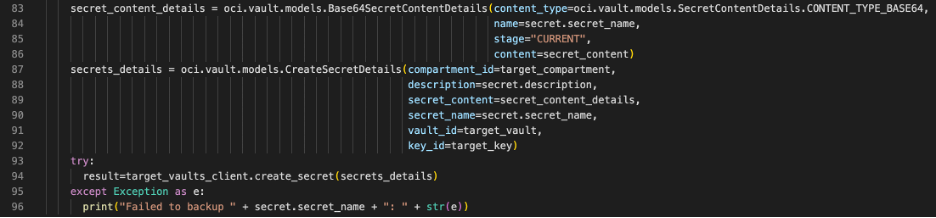

Assuming the secret you pulled from the source vault doesn’t already exist in the target, it’s time to create one. We create the content_details and secret_details, like the update process. The difference is that secret_details needs more information when creating.

That’s all it takes!

That’s the process. I glossed over various details, but the goal is to get going quickly with a customizable process. Take the following information into consideration.

I didn’t do a ton of error trapping, but you might want to think it over and expand. My logging for errors is simplistic—print statements. You can expand and consider integrating into your favorite logging or alerting capability for batch processing. You can easily set up vaults as an OCI function that takes some of the defined variables as inputs. I run mine on a schedule using Oracle Container Engine for Kubernetes and the Kubernetes cron capabilities.

Think about your backup strategy, particularly how you want it defined in your target region. Is it all one big vault, or do you have a one-to-one relationship of source to target vaults? You might need to get a service limit increase if you have a lot of versions and vaults.

You can find the code shown in this blog on GitHub.

Link to Key Management with OCI Vault.