Encryption is a basic need for managing your data in the cloud. Security sensitive workloads often use cryptographic keys stored in specialized hardware known as hardware security modules (HSM) for encryption. Cloud providers offer key management services (KMS) using such HSMs. Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI) Vault lets customers centrally manage and control use of cryptographic keys and secrets across a wide range of OCI services and applications. OCI Vault is a secure, resilient, managed service that lets customers focus on their data encryption needs without worrying about time-consuming administrative tasks, such as hardware provisioning, software patching, and high availability.

Availability, resilience, and durability of cryptographic keys and the respective services are critical because they encrypt customer’s application data. Our customers can backup their keys in Vault to a cold storage and restore them later.

With the launch of cross-regional replication of keys, customers now have the flexibility to recover from complete regional failures by replicating their keys between any two regions in OCI including the Government Cloud and Oracle Cloud@Customer. When replication is enabled, we automatically replicate existing and new keys with associated metadata and provide accurate replication status. This replication also enables customers to use storage applications like Oracle DataGuard with primary and standby databases encrypted with a KMS key in any two regions in OCI public and Government cloud.

These features required solving some hard engineering problems around fault tolerant geographic data replication. In this blog, we describe some of these problems and our approaches to tackle them. Before describing the solutions, you need to understand the following foundational concepts:

-

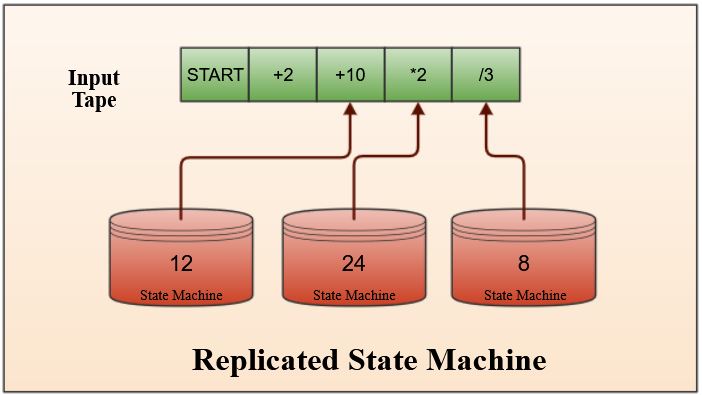

State machine: A state machine is a behavior model that consists of a finite number of states. Based on the current state and an input, the machine performs state transitions and produces outputs.

-

Replicated state machine (RSM): A replicated state machine allows multiple state machines to work off the same set of inputs and produce similar outputs.

-

Hardware security module (HSM): A hardware security module (HSM) is a physical computing device that safeguards and manages digital keys and performs encryption and decryption functions for digital signatures, strong authentication, and other cryptographic functions.

-

Write-ahead log (WAL): Write-ahead logs provide atomicity and durability (two of the ACID properties) in database systems. The changes are first recorded in the log, which must be written to stable storage, before the changes are written to the database.

-

OCI Realm: Oracle Cloud Infrastructure public, Government, and Cloud@Customer regions are grouped into respective OCI realms.

HSM Replication

Consider the example of modeling a calculator as a state machine. The inputs are read off a tape, an arithmetic operation is performed from the command in the input, and the resulting output is persisted. When queried, it provides the latest persisted output. A state machine provides the same output at any given point in the input tape regardless of how many times the tape is applied. This deterministic property is desirable for modeling many real-world systems as state machines. Our calculator is one such system, although real world systems need to be resilient to failures and require more than a single state machine to operate.

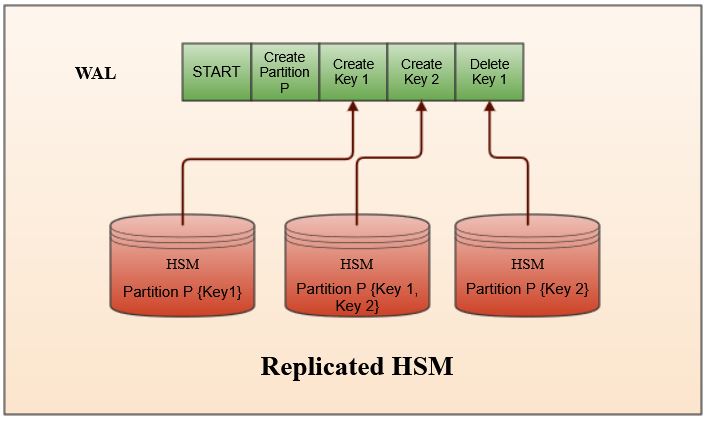

Modeling HSMs as RSMs

OCI Key Management Service uses HSMs that meet Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) 140-2 Security Level 3 security certification to store customer keys. Each HSM consists of several partitions that provide a logical and security boundary for the keys stored in them. When customers create a vault, the vault has an associated partition, and all the keys inside the vault are created in that partition. You can’t share the contents of one partition with another unless they share the same chain of trust. This feature keeps our security blast radius local to a single partition.

We model our HSMs as RSMs. Each customer-facing vault has an associated WAL. This WAL records customer operations on their vault including but not limited to creation, deletion of keys, and any metadata updates. We store the WALs in an internal OCI durable key-value store that supports transactional reads and writes. Similar to the calculator, a customer vault can be fully recreated from nothing by applying the entries in WAL associated with the vault. To provide a sense of scale, we deal with thousands of WALs with millions of entries in many of them.

Replicating HSM

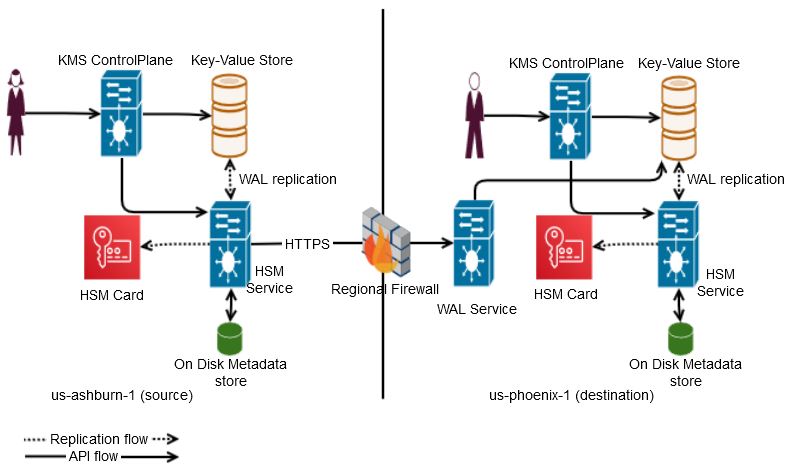

When a customer creates a vault, the associated partition in HSM is replicated across hosts in data centers within a region by default. With cross-regional replication enabled on the vault, we relay the WAL to the destination region and apply to all the hosts in that region. For example, by default in the us-ashburn-1 region, customer keys are replicated to hosts distributed across three data centers. KMS services in a region run behind a firewall and are connected through an internal network with limited access to internet through a set of trusted proxy hosts.

To enable cross-regional communication, we run a high performant RESTful service called WAL service in each region that takes WAL traffic from KMS services in other regions within an OCI realm. The cross-regional calls from one region to the WAL service in another region goes through the trusted proxies at the edge of source region. The following figure shows the data flow from one region to another. All the services are RESTful, distributed geographically, and run behind multiple load balancers.

Geographic replication

OCI KMS has various distributed services that work together within and across the regional boundaries. However, the complexity in most geo replicated systems comes from dealing with Byzantine faults. We had to account for the following failure scenarios in our design:

-

Incidents leading to partial or full loss of hosts, disks, data stores, HSMs, and any medium that keeps customer data in general

-

Network issues that lead to data corruption in-transit, out-of-order delivery of messages, and partitions

-

Complex bugs or incidents leading to poison pills in our WALs and permanent data center disasters

To tackle these problems, we’ve built a handful of invariants in our replication system, including the following critical examples:

Stateless services

The WAL entries encode all the system states related to the corresponding customer vault so that our services can be stateless. Each WAL entry contains both customer data and metadata about our infrastructure. This configuration simplifies the disaster recovery process.

Log sequence number (LSN)

An LSN is monotonically dense and increasing. Each WAL entry has an associated LSN and entries are ordered by it.

RegionShardId

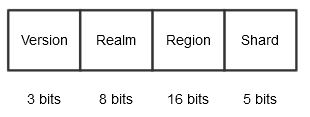

OCI KMS is a sharded system where we scale each region horizontally. A regionShardId encodes the combination of OCI realm, region, and KMS shard in an integer. We have a unique 32-bit integer, representing each shard across regions and realms. This process is space- and compute-efficient because we can retrieve information about WAL’s membership by doing fast bit operations.

For example, you can obtain region information with the following command:

REGION_SHIFT = 5 // we need to shift last 5 bits to push region bits to the end region = regionShardId >> REGION_SHIFT & ((1 << 16) - 1); // Now apply a bit mask of length 16 (region bits length) to extract it outSimilarly with individual components, we compute a regionShardId with the following command:

regionShardId = ((realmId & ((1 << 8) - 1)) << 21) | ((regionId & ((1 << 16) - 1)) << 5) | ((shardId & ((1 << 5) - 1)) << 0) | ((version & ((1 << 3) - 1)) << 29)21, 5, 0 and 29 are the number of bit shifts required after applying bit masks to each component as described in the described order.

8, 16, 5 and 3 are number of bits required to represent realm, region, shard, and version.

Log matching

We need a fast way to compare two WALs at a point and say whether they’re the same until that point (log matching property). So, we calculate incremental checksum of each log entry and compare the actual and computed checksum values during replication. If the checksum of WAL W1 at point ’n’ matches with another WAL W2 at ’n,’ then W1 and W2 have same set of entries until ’n.’

This invariant helps us identify bit flips during transit, resolve conflicts, and converge WALS between regions after a disaster.

Membership info

WAL entries encode membership info as an ordered set of regionShardIds. When a customer adds or removes a replica for a vault, the WAL’s membership set is updated with that regionShardId info. Each WAL entry has the membership info encoded, and the last entry in the WAL contains the most recently known membership. At least a single entry with membership info is kept even after we snapshot and truncate a WAL.

This setup helps us recreate a vault in a region purely from a replicated WAL after a permanent disaster. It gives us both customer data and metadata about our infrastructure. Each WAL entry also encodes the id of the primary region for the WAL.

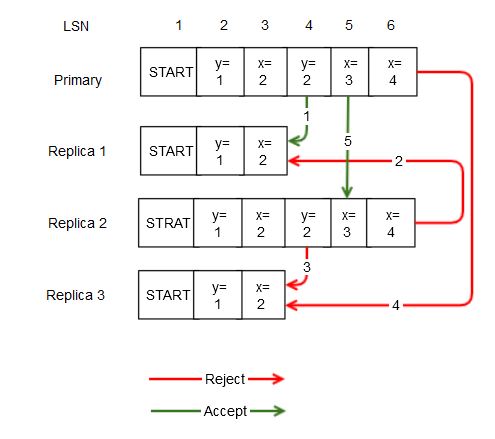

To put all this information in perspective, each WAL can accept and reject the following scenarios:

Let’s say that we have a primary region and three other replica regions 1, 2, and 3. The following operations are valid or invalid:

-

Primary replicating log entry with LSN 4 to Replica 1: Valid operation

-

Replica 2 replicating log entry with LSN 6 to Replica 1: Invalid checksum because of bad LSN and primary’s region id

-

Replica 2 replicating entry with LSN 4 to Replica 3: Invalid checksum because of bad primary region id

-

Primary replicating entry with LSN 6 to Replica 3: Invalid checksum because of bad LSN

-

Primary replicating entry with LSN 5 to Replica 2: Valid operation

With these invariants, we resolve conflicts among WALs by binary searching for the latest LSN at which the checksum matches for all conflicting WALs and overwrite the values from the current primary region with most up-to-date WAL entries.

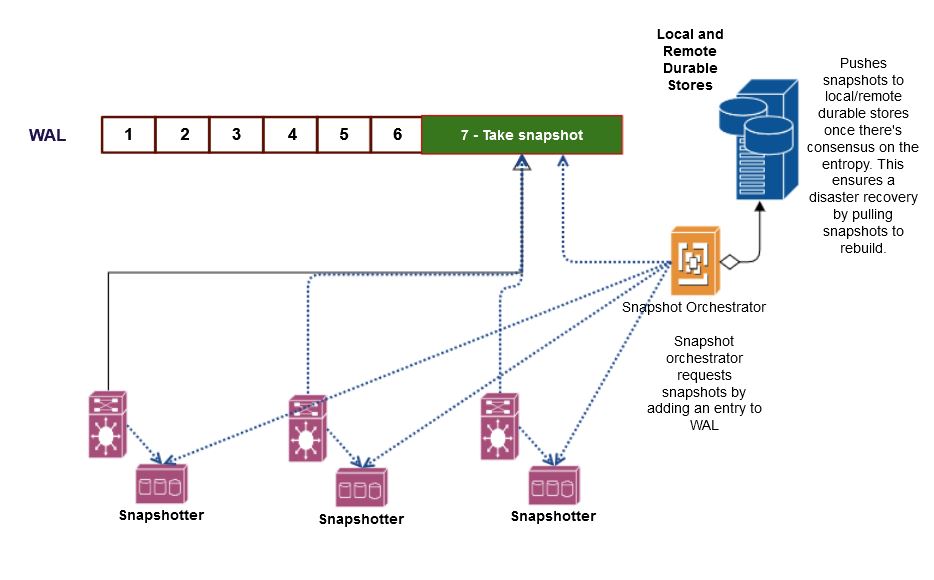

Snapshotting

I mentioned earlier that our WALs have millions of entries. It’s inefficient to apply all of them every time that we need to bootstrap a host or set up cross-regional replication for a customer vault. So, we snapshot our WALs every 30 minutes and based on the rate of growth of WAL entries. We can fully recover our services and data in a region from the snapshots. With snapshotting, a vault with over a million WAL entries can be rebuilt under a few seconds. To make it robust, snapshots are cross regionally copied by default and kept in two different regions for redundancy.

Earlier, I touched on driving both customer data and infrastructure updates through the same WAL. Snapshotting is one such infrastructure update that’s driven through the WALs. This process allows us to take the snapshot of underlying state machine exactly at the same point on all the hosts.

Snapshot correctness

Each snapshot has an entropy value associated with it, which is computed from the checksum of data within. We take snapshots on every state machine at the same point and a centralized snapshot orchestrator compares the entropy values and promotes a snapshot as valid only after consensus. We also need to ensure that no bit flips occur during transit to a durable store, so we checksum the entire snapshot and ensure that what we store is what we intend to.

Monitoring

We talked a lot about dealing with failures and disasters. But how do you guarantee customers that the data you serve from every host is correct? For example, a customer creates a key at time T1 and deletes the same at T2. If a host isn’t caught up to T2, it shouldn’t serve traffic on that deleted key.

We run a lease based daemon named cluster manager that continuously monitors all the hosts and takes inactive (degraded) hosts out of load balancers. This prevents stale nodes from serving any customer traffic. Cluster manager is responsible for committing the key and vault mutations based on replication progress on all the healthy nodes within each region. This is tracked by a commit index per WAL which moves forward every time a WAL entry is persisted on all of the healthy nodes in the cluster. Anytime the number of healthy nodes fall below the configured quorum size on each region, cluster manager stalls the movement of the commit index on each WAL. This guarantees a key will be made available to customers in a region if and only if it is available on a quorum of nodes in that region. In addition, the cluster manager also alerts us if we start seeing laggy replicas on one or more WALs or a quorum loss, indicating degraded customer experience within 5 minutes. In practice we’ve found this delay to be adequate for a service like KMS, where customer mutations on their keys and vaults aren’t frequent.

Security

Everything that we’ve talked about so far is done with customer keys never leaving the cryptographic boundary on the HSM. Anything that comes out of HSM for replication is encrypted by a chain of trust rooted at associated partition in the HSM. All our snapshots are encrypted with AES 256-bit keys using GCM wrapped by 4096-bit RSA keys using RSA-OAEP whose trust is rooted at HSM. All the sensitive customer data and metadata are encrypted in our data stores using an internal key belonging to the customer’s vault. Our design invariant is that any sensitive customer data in our premises need protection by the same customer vault that’s protecting customer’s application data.

Formal verification

Everything works well in practice, but is that enough? Distributed systems work successfully until a real-world edge case causes a catastrophic outage, much worse customer data loss. We worked with our verification engineers to build a formal verification model using TLA+ for everything we talked about in this post. Every time our replication platform is updated, we ensure that the model doesn’t break by running a full suite of backward-compatibility tests. If we don’t validate the long tail of rare edge cases regularly, we assume that our code to handle them doesn’t work when it needs to.

Conclusion

Our security services are experiencing rapid growth with customer usage. This growth throws a lot of interesting challenges on our way every day. We’re constantly thinking about 100 times our current usage, given the rate at which OCI services are being consumed. I’ve only scratched the surface of what we’ve built in OCI KMS to showcase how we solve distributed system problems at scale. At Oracle Cloud Infrastructure, we take pride in solving hard problems if that’s the right thing to do for our customers.