A few months back, I read a really excellent (but pretty old) blog post that explained how to hack a toy called a Mind Flex to extract and analyze the data within it. At first, I couldn’t believe that such a thing existed. I mean, sure – gimmicky toys have been around for ages, so I wasn’t shocked that the toy claimed to read the user’s mind. It’s not uncommon to fake this kind of gimmick. But, the fact that the Mind Flex contains a real, legit EEG chip that read your mind seemed almost too good to be true. I wondered if it was possible to take this hack a step further. Instead of just reading the data, or using the data to “control” something else, what if I were to read the data while performing some task and see what the data reveals about my performance during that task? I would need to complete an activity with quantifiable data to properly compare the brain activity to the task results to see if my attention levels correlated to the task’s success or failure. Deciding on the actual action to measure wasn’t tricky. I am a pretty avid video game player and had recently been trying to think of a way to integrate my gameplay statistics into a project, so I surmised that the combination would be an intriguing one.

So I asked myself: “if I could hack the Mind Flex and wear it while playing Call of Duty, what would the data show?” Could I establish a relationship between cognitive function and video game performance? In other words, when I’m focused and attentive, do I play better? Or, when I’m distracted, do I play worse? Is there no connection at all? I wasn’t sure if my tests would succeed, but I decided to find out.

Video Overview

If you would like to watch an entertaining interpretation of this blog post, check out the following YouTube video.

Asking Questions

Once I established the idea for the project, I started asking myself some questions:

- Can I read my brain data?

- If so, is the data valid?

- Can I improve my performance in video games by being super focused and concentrating?

- If I’m distracted, will I play poorly?

- Will a “bad game” be visible in my brain activity?

- Is there a direct, measurable relationship between superior gaming performance and high levels of attention?

- Or, are there just too many factors at play?

Objectives

To answer those questions, I decided to establish a few objectives for the project:

- Capture my brain data (at home) in an accurate and cost-effective manner

- Establish a “baseline” mental state

- Capture my brain data while playing a video game

- Quantify my video game performance (via data)

- Establish and visualize a relationship between the cognitive measures and my game performance

Now I should mention that constraints and outside factors come into play. Things like server/network latency, “skill-based matchmaking,” opponents’ skill-level, and other unknowns. Could those external factors be excluded? The outside factors concerned me a bit, but I decided to move forward and let the data tell me a story.

The Hypothesis

Since I decided to take a “scientific” approach to this, I decided that it made sense to establish a hypothesis. The hypothesis that I agreed upon is as follows:

The more focused I am, the better I will perform at a multiplayer “first-person shooter” (Call of Duty: Vanguard). Conversely, my gameplay will be negatively impacted by a lack of focus and attention.

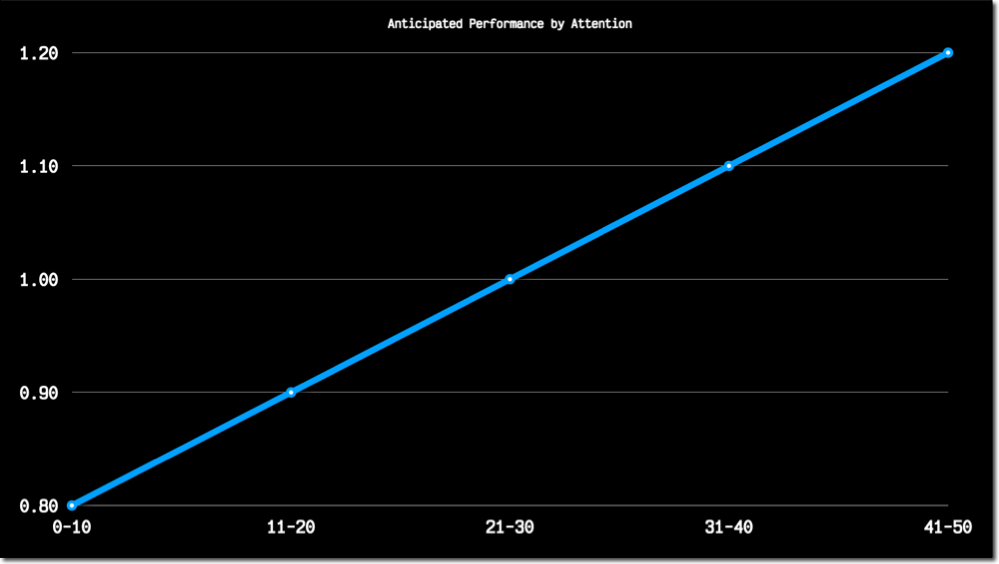

This hypothesis made sense to me at the time when I established it. I figured there would be a linear correlation between my attention levels and video game performance. Indeed, the more I pay attention, the better I will score, right? I assumed the data would ultimately look like this:

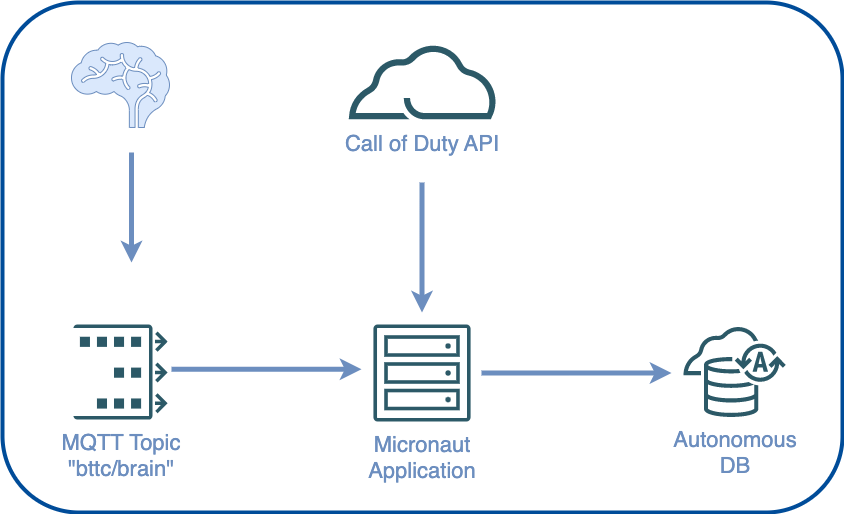

The Architecture

I would need to obtain and hack a Mind Flex to test my hypothesis. I decided to use a much smaller ESP-12 board instead of the Arduino board that the original blog post used because the ESP-12 board contains onboard WiFi, and I figured I’d be able to keep it self-contained inside the Mind Flex housing. So my approach was to use the Mind Flex to capture my brain activity by connecting the “transmit” pin on the EEG chip to the “receive” pin on the ESP board and program the board to upload the readings to an MQTT topic. Here’s how the ESP board looked once I soldered it to the EEG chip.

Separately, I’d need to capture my videogame stats via scheduled calls to the “unofficial” Call of Duty API. I created a Micronaut application and deployed it to the cloud to do that, with a task that runs every hour to persist the data into my Autonomous DB instance.

Let’s pause for a small commercial break…

What if I told you that the entire architecture you see above was straightforward to create and deploy in the cloud? That’s right, the MQTT broker, the Micronaut application deployed to a VM instance, and the Autonomous Database instance! All cloud-based and easy to manage and maintain! What do you think you’d have to pay for such an architecture? But wait, there’s more! What if I told you that object storage, database backups, and VM backups were all included? Sounds too good to be true, right? Well, it is true. And not only do you get all that, but you can get it today (or tomorrow, or the next day) for the low-low price of $0.00. That’s right – ZERO dollars and ZERO cents! That’s because this entire architecture can be yours on the Oracle Cloud always-free tier! Sign up today at https://cloud.oracle.com/free!

…and now back to our regularly scheduled blog post.

For maximum flexibility, I decided to store the video game stats in the raw JSON form, which would be easy to work with from SQL later on. Once the application had stored my videogame stats and brain activity in the database, I’d be able to write some queries to combine the data based on the match start/end timestamps joined to the brain capture timestamps—more on that in just a bit.

Summary

In this post, I introduced you to my Brain to the Cloud project and talked about the inspiration, objectives, hypothesis, and an overview of the architecture. In the next post, we’ll take a deep dive into the technical side of this project. If you’d like to check out the project in more detail, check out my project site at https://bttc.toddrsharp.com.