Error management and exception handling in PL/SQL October 2020

Part 6 in a series of articles on understanding and using PL/SQL for accessing Oracle Database

PL/SQL is one of the core technologies at Oracle and is essential to leveraging the full potential of Oracle Database. PL/SQL combines the relational data access capabilities of the Structured Query Language with a flexible embedded procedural language, and it executes complex queries and programmatic logic run inside the database engine itself. This enhances the agility, efficiency, and performance of database-driven applications.

Steven Feuerstein, one of the industry’s best-respected and most prolific experts in PL/SQL, wrote a 12-part tutorial series on the language. Those articles, first published in 2011, have been among the most popular ever published on the Oracle website and continue to find new readers and enthusiasts in the database community. Beginning with the first installment, the entire series is being updated and republished; please enjoy!

Even if you write absolutely perfect PL/SQL programs, something may go wrong and an error will occur when those programs are run. How your code responds to and deals with such errors often spells the difference between a successful application and one that creates all sorts of headaches for users as well as developers.

This article explores the world of error management in PL/SQL: the different types of exceptions you may encounter; when, why, and how exceptions are raised; how to define your own exceptions; how you can handle exceptions when they occur; and how you can report information about problems back to your users.

Exception overview

There are three categories of exceptions in PL/SQL: internally defined, predefined, and user defined.

An internally defined exception is one that is raised internally by an Oracle Database process; this kind of exception always has an error code but does not have a name unless it is assigned one by PL/SQL or your own code. An example of an internally defined exception is ORA-00060 (deadlock detected while waiting for resource).

A predefined exception is an internally defined exception that is assigned a name by PL/SQL. Most predefined exceptions are defined in the STANDARD package (a package provided by Oracle Database that defines many common programming elements of the PL/SQL language) and are among the most commonly encountered exceptions. One example is ORA-00001, which is assigned the name DUP_VAL_ON_INDEX in PL/SQL and is raised when a unique index constraint is violated.

A user defined exception is one you have declared in the declaration section of a program unit. User defined exceptions can be associated with an internally defined exception (that is, you can give a name to an otherwise unnamed exception) or with an application-specific error.

Every exception has an error code and an error message associated with it. Oracle Database provides functions for retrieving these values when you are handling an exception (see Table 1).

| Description | How to get it |

|---|---|

| The error code. This code is useful when you need to look up generic information about what might cause such a problem. | SQLCODE Note: You cannot call this function inside a SQL statement. |

| The error message. This text often contains application-specific data such as the name of the constraint or the column associated with the problem. | SQLERRM or DBMS_UTILITY.FORMAT_ERROR_STACK Note: You cannot call SQLERRM inside a SQL statement. |

| The line on which the error occurred. This capability was added in Oracle Database 10g Release 2 and is enormously helpful in tracking down the cause of errors. | DBMS_UTILITY.FORMAT_ERROR_BACKTRACE |

| The execution call stack. This answers the question “How did I get here?” and shows you the path through your code to the point at which DBMS_UTILITY.FORMAT_CALL_STACK is called. | DBMS_UTILITY.FORMAT_CALL_STACK |

Table 1: Where to find error information in PL/SQL applications.

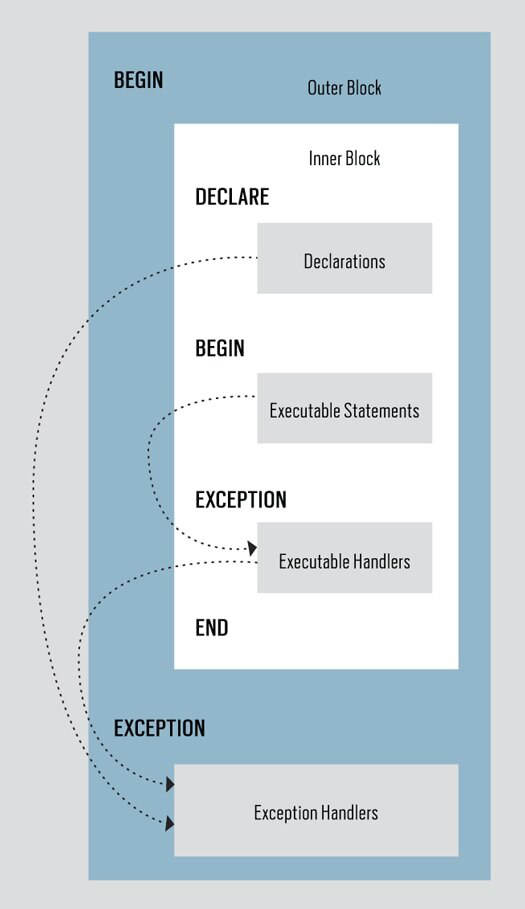

A PL/SQL block can have as many as three sections: declaration, executable, and exception. (See Part 1 of this series, “Building with blocks,” for more information on PL/SQL blocks.) When an exception is raised in the executable section of a block, none of the remaining statements in that section is executed. Instead, control is transferred to the exception section.

The beauty of this design is that all exception-related activity is concentrated in one area in the PL/SQL block, making it easy for developers to understand and maintain all error management logic. Let’s look at the flow of execution in a block when an error occurs (see Figure 1). The process of raising exceptions and the structure of the exception section are described more fully later in this article.

Figure 1: Exception propagation

If a WHEN clause in the exception section catches that exception, the code in that clause will be executed, usually logging information about the error and then reraising that same exception.

If the exception is not caught by the exception section or there is no exception section, that exception will propagate out of that block to the enclosing block; it will be unhandled. Execution of that block will then terminate, and control will transfer to the enclosing block’s exception section (if it exists).

Raising exceptions

In most cases when an exception is raised in your application, Oracle Database will do the raising. That is, some kind of problem has occurred during the execution of your code and you have no control over this process. Once the exception has been raised, all you can do is handle the exception—or let it “escape” unhandled to the host environment.

You can, however, raise exceptions in your own code. Why would you want to do this? Because not every error in an application is due to a failure of internal processing in the Oracle Database instance. It is also possible that a certain data condition constitutes an error in your application, in which case you need to stop the processing of your algorithms and, quite likely, notify the user that something is wrong.

PL/SQL offers two mechanisms for raising an exception:

- The RAISE statement

- The RAISE_APPLICATION_ERROR built-in procedure

The RAISE statement. You can use the RAISE statement to raise a user defined exception or an Oracle Database predefined exception. In the following example, I have decided that if the user has supplied a NULL value for the department ID, I will raise the VALUE_ERROR exception:

CREATE OR REPLACE PROCEDURE

process_department (

department_id_in IN INTEGER)

IS

BEGIN

IF department_id_in IS NULL

THEN

RAISE VALUE_ERROR;

END IF;

You can also use RAISE to reraise an exception from within the exception section (see “Handling exceptions” for an example).

RAISE_APPLICATION_ERROR. The RAISE statement raises an exception, stopping the current block from continuing. It also sets the current error code and error message. This error message—such as “ORA-06502: PL/SQL: numeric or value error”—is supplied by Oracle Database and is usually generic.

This kind of error message might be sufficient for reporting database errors, but what if an application-specific error—such as “Employee is too young” or “Salary cannot be greater than $1,000”—has been raised? A “Numeric or value error” message is not going to help users understand what they did wrong and how to fix it.

If you need to pass an application-specific message back to your users when an error occurs, you should call the RAISE_APPLICATION_ERROR built-in procedure. This procedure accepts an integer (your error code), whose value must be between -20,999 and -20,000, and a string (your error message).

When this procedure is run, execution of the current PL/SQL block halts immediately and an exception (whose error code and message are set from the values passed to RAISE_APPLICATION_ERROR) is raised. Subsequent calls to SQLCODE and SQLERRM will return these values.

Here is an example of using RAISE_APPLICATION_ERROR: An employee must be at least 18 years old. If the date of birth is more recent, raise an error so that the INSERT or UPDATE is halted, and pass back a message to the user:

CREATE OR REPLACE PROCEDURE

validate_employee (

birthdate_in IN DATE)

IS

BEGIN

IF birthdate_in >

ADD_MONTHS (SYSDATE, -12 * 18)

THEN

RAISE_APPLICATION_ERROR (-20500

, 'Employee must be at least

18 years old.');

END IF;

END;

Defining your own exceptions

There are two reasons you might want to define your own exception (that is, employ a user defined exception): to give a name to an error that was not assigned a name by Oracle Database or to define an application-specific exception such as “Balance too low.”

To define your own exception, use the EXCEPTION data type, as in

DECLARE e_balance_too_low EXCEPTION;

By default, the error code associated with this exception is 1 and “User Defined Error” is the error message. You can, however, associate a different error code with your exception by using the EXCEPTION_INIT pragma. In the block below, I have decided to associate the “Balance too low” error with code -20,000.

CREATE OR REPLACE PROCEDURE

process_balance (

balance_in IN NUMBER)

IS

e_balance_too_low EXCEPTION;

PRAGMA EXCEPTION_INIT (

e_balance_too_low, -20000);

BEGIN

IF balance_in < 1000

THEN

RAISE e_balance_too_low;

END IF;

END;

Handling exceptions

Oracle Database might raise an internal or predefined exception, and you can also explicitly raise an exception you’ve defined for your application. It’s your job to decide how you want your program to handle that exception.

If you don’t want an exception to leave your block or subprogram before it is handled, you must include an exception section that will catch the exception. The exception section starts with the keyword EXCEPTION and then contains one or more WHEN clauses. A WHEN clause can specify a single exception (by name), multiple exceptions connected with the OR operator, or any exception.

Here are some examples of WHEN clauses:

- Catch the NO_DATA_FOUND exception, usually raised when a SELECT-INTO statement is executed and finds no rows:

WHEN NO_DATA_FOUND THEN

- Catch either the NO_DATA_FOUND or DUP_VAL_ON_INDEX predefined exceptions:

WHEN NO_DATA_FOUND OR DUP_VAL_ON_INDEX THEN - Catch any exception:

WHEN OTHERS THEN

You can have multiple WHEN clauses in your exception section, but if you have a WHEN OTHERS clause, it must come at the end.

It’s easy enough to define one or more WHEN clauses. The trickier part of the exception section is deciding what to do after you have caught an exception. Generally, code in an exception handler should perform the following two steps:

- Record the error in some kind of log, usually a database table.

- Raise the same exception or a different one, so it propagates unhandled to the outer block.

Reraising exceptions. You could simply record information about an error and then not reraise the exception. The problem with this approach is that your application has “swallowed up” an error. The user (or the script that is being run) will not know that there was a problem. In some scenarios, that may be OK, but they are very rare. In almost every situation when an error occurs, you really do want to make sure that the person or the job running the code that raised the error is informed.

Oracle Database makes it easy to do this with the RAISE statement. If you use RAISE in an executable section, you must specify the exception you are raising, as in

RAISE NO_DATA_FOUND;

But inside an exception handler, you can also use RAISE without any exception, as in

RAISE;

In this form, Oracle Database will reraise the current exception and propagate it out of the exception section to the enclosing block.

Note that if you try to use RAISE outside of an exception section, Oracle Database will raise a compile-time error:

PLS-00367: a RAISE statement with no exception name must be inside an exception handler

Recording errors. Suppose something’s gone wrong in your application and an exception was raised. You can certainly just let that exception propagate unhandled all the way out to the user, by not writing any exception sections in your subprograms. Users will then see the error code and message and either report the problem to the support team or try to fix the problem themselves.

In most cases, however, you’d like to store the information about the error before it is communicated to the user. That way you don’t have to rely on your users to give you information such as the error code or the error message.

When you record your error, you should include the information shown in Table 1, all of which is obtainable through calls to functions supplied by Oracle Database. All of this information will help a developer, or a member of the support team, diagnose the cause of the problem. You may, in addition, want to record values of application-specific data, such as variables or column values.

If you decide to store your error information in a table, you should not put the INSERT statements for the error log table directly inside your exception. Instead, you should build and call a procedure that does this for you. This process of “hiding” the way you implement and populate your log will make it easier and more productive to log errors.

To understand these advantages, let’s build a simple error log table and try using it in my exception section. Suppose my error log table looks like this:

CREATE TABLE error_log ( ERROR_CODE INTEGER , error_message VARCHAR2 (4000) , backtrace CLOB , callstack CLOB , created_on DATE , created_by VARCHAR2 (30) )

I could write an exception handler as shown in Listing 1.

Code listing 1: Exception handling section inserting into log table

EXCEPTION

WHEN OTHERS

THEN

DECLARE

l_code INTEGER := SQLCODE;

BEGIN

INSERT INTO error_log (error_code

, error_message

, backtrace

, callstack

, created_on

, created_by)

VALUES (l_code

, sys.DBMS_UTILITY.format_error_stack

, sys.DBMS_UTILITY.format_error_backtrace

, sys.DBMS_UTILITY.format_call_stack

, SYSDATE

, USER);

RAISE;

END;

No matter which error is raised in my program, this handler will catch it and store lots of extremely useful information about that error in my table.

I strongly suggest, however, that you never write exception handlers like this. Problems include

- Too much code. You have to write lots of code to store the error information. This leads to reduced productivity or fewer exception handlers (programmers don’t feel that they have to write all this code, so they rationalize away the need to include a handler).

- The error log becomes part of a business transaction. I inserted a row into a table. I know that this table is different from the “real” tables of the application (for example, the Employees table of the human resources application). But Oracle Database makes no distinction. If a rollback is performed because of the error, the INSERT into the log table will also be rolled back.

- Brittle code. If I ever need to change the structure of the error_log table, I will have to change all the INSERT statements to accommodate this change.

A much better approach is to “hide” the table behind a procedure that does the INSERT for you, as shown in Listing 2.

Code listing 2: Exception handling procedure inserting into log table

CREATE OR REPLACE PROCEDURE record_error

IS

l_code PLS_INTEGER := SQLCODE;

l_mesg VARCHAR2(32767) := SQLERRM;

BEGIN

INSERT INTO error_log (error_code

, error_message

, backtrace

, callstack

, created_on

, created_by)

VALUES (l_code

, l_mesg

, sys.DBMS_UTILITY.format_error_backtrace

, sys.DBMS_UTILITY.format_call_stack

, SYSDATE

, USER);

END;

All I’ve done is move the INSERT statement inside a procedure, but that simple action has important consequences. I can now very easily get around the problem of rolling back my error log INSERT along with my business transaction. All I have to do is make this procedure an autonomous transaction by adding the pragma statement and the COMMIT, as shown in Listing 3.

Code listing 3: Exception handling procedure as autonomous transaction with COMMIT

CREATE OR REPLACE PROCEDURE record_error

IS

PRAGMA AUTONOMOUS_TRANSACTION;

l_code PLS_INTEGER := SQLCODE;

l_mesg VARCHAR2(32767) := SQLERRM;

BEGIN

INSERT INTO error_log (error_code

, error_message

, backtrace

, callstack

, created_on

, created_by)

VALUES (l_code

, l_mesg

, sys.DBMS_UTILITY.format_error_backtrace

, sys.DBMS_UTILITY.format_call_stack

, SYSDATE

, USER);

COMMIT;

END;

By declaring the procedure to be an autonomous transaction, I can commit or roll back any of the changes I make to tables inside this procedure without affecting other changes made in my session. So I can now save the new row in my error log, and a later rollback of the business transaction will not wipe out this information.

With this logging procedure defined in my schema, I can write an exception handler as follows:

EXCEPTION

WHEN OTHERS

THEN

record_error();

RAISE;

It takes me much less time to write my exception handler, and its functionality is more robust. A win-win situation!

Exceptions raised while declaring. If an exception is raised in the declaration section of a block, the exception will propagate to the outer block. In other words, the exception section of a block can catch only exceptions raised in the executable section of the block.

The following block includes a WHEN OTHERS handler, which should trap any exception raised in the block and simply display the error code:

DECLARE

l_number NUMBER (1) := 100;

BEGIN

statement1;

...

statementN;

EXCEPTION

WHEN OTHERS

THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.put_line (SQLCODE);

END;

When I execute the block, Oracle Database will try to assign the value 100 to l_number. Because it is declared as NUMBER (1), however, 100 will not “fit” into the variable. As a result, Oracle Database will raise the ORA-06502 error, which is predefined in PL/SQL as VALUE_ERROR.

Because the exception is raised in the process of declaring the variable, the exception handler will not catch this error. Instead I’ll see an unhandled exception:

ORA-06502: PL/SQL: numeric or value error: number precision too large ORA-06512: at line 2

Consequently, you should avoid assigning values to variables in the declaration section unless you are certain that no error will be raised. You can, instead, assign the value in the executable section, and then the exception handler can trap and record the error:

DECLARE

l_number NUMBER (1);

BEGIN

l_number := 100;

statement1;

...

statementN;

EXCEPTION

WHEN OTHERS

THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.put_line (SQLCODE);

END;

Exceptions and rollbacks

Unhandled exceptions do not automatically result in the rollback of outstanding changes in a session. Indeed, unless you explicitly code a ROLLBACK statement into your exception section or the exception propagates unhandled to the host environment, no rollback will occur. Let’s look at an example.

Suppose I write a block of code that performs two data manipulation language (DML) operations:

- Remove all employees from the Employees table who are in department 20.

- Give a raise to all remaining employees by multiplying their current salary by 200.

That is very generous, but the constraint on the salary column is defined as NUMBER(8,2). The salary of some employees is already so large that the new salary amount will violate this constraint, leading Oracle Database to raise the “ORA-01438: value larger than specified precision allowed for this column” error.

Suppose I run the following block in a SQL*Plus session:

BEGIN

DELETE FROM employees

WHERE department_id = 20;

UPDATE employees

SET salary = salary * 200;

EXCEPTION

WHEN OTHERS

THEN

DECLARE

l_count PLS_INTEGER;

BEGIN

SELECT COUNT (*)

INTO l_count

FROM employees

WHERE department_id = 20;

DBMS_OUTPUT.put_line (l_count);

RAISE;

END;

END;

The DELETE is completed successfully, but then Oracle Database raises the ORA-01438 error when trying to execute the UPDATE statement. I catch the error and display the number of rows in the Employees table WHERE department_id = 20. “0” is displayed, because the failure of the UPDATE statement did not cause a rollback in the session.

After I display the count, however, I reraise the same exception. Because there is no enclosing block and this outermost block terminates with an unhandled exception, any changes made in this block are rolled back by the database.

So after this block is run, the employees in department 20 will still be in the table.

Warning, no reraise!

Oracle Database 11g Release 1 added a very useful warning to its compile-time warning subsystem: “PLW-6009: handler does not end in RAISE or RAISE_APPLICATION_ERROR.”

In other words, the compiler will now automatically detect exception handlers that might be “swallowing up” an error, by not propagating it to the enclosing block.

Here is an example:

SQL> ALTER SESSION SET plsql_warnings = 'ENABLE:6009'

2 /

Session altered.

SQL> CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION plw6009

2 RETURN VARCHAR2

3 AS

4 BEGIN

5 RETURN 'abc';

6 EXCEPTION

7 WHEN OTHERS

8 THEN

9 RETURN NULL;

10 END plw6009;

11 /

SP2-0806: Function created with compilation warnings

SQL> show errors

Errors for FUNCTION PLW6009:

LINE/COL ERROR

-------- -------------------------------

7/9 PLW-06009: procedure

"PLW6009" OTHERS handler

does not end in

RAISE or RAISE_APPLICATION_ERROR

This is a very helpful warning, with one caveat: If I call an error logging procedure that itself calls RAISE or RAISE_APPLICATION_ERROR to propagate an unhandled exception, the compiler will not recognize this and will still issue the PLW-6009 warning for the subprogram.

Next time: The record data type

PL/SQL provides a wide range of features to help you catch and diagnose errors as well as communicate application-specific errors to your users. The exception section makes it easy to centralize all your exception handling logic and thereby manage it more effectively.

In the next PL/SQL 101 article, I will explore the record data type in PL/SQL, the use of the %ROWTYPE anchor, how you can declare and use your own record types, record-level inserts and updates, and more.